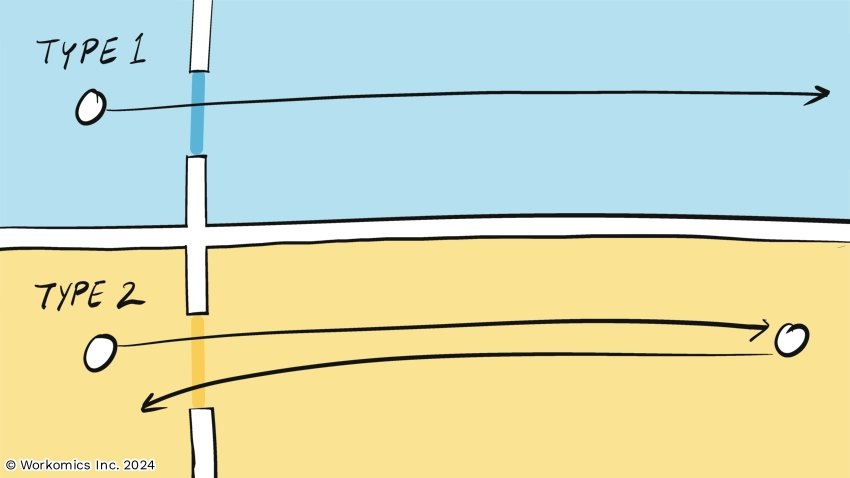

You may be familiar with this typology of decisions from Jeff Bezos’s 2015 Letter to Amazon Shareholders:

- Type 1 Decisions are not easily reversed — “one-way doors.” These decisions should be made with ample consultation and careful consideration of wide-reaching implications.

- Type 2 Decisions are easily reversed — “two-way doors.” If we make this decision and don’t like the outcome, we can always go back through the door. These decisions should be made quickly. Rather than spend a lot of time carefully weighing theoretical risks, the decision can be implemented and we can see the real-world data.

Bezos’s observation is that as companies grow, they have an increasing tendency to use a long, slow Type 1 decision-making process on easily-reversible Type 2 decisions. It’s one of the things that makes large companies more risk-averse and less nimble than their smaller counterparts.

Sample caption in relation to the image above which is very pretty - ohhhh (image credit: someone out there)

Of course, in the real world, there isn’t a neat dichotomy. Is getting married an “easily reversible” decision? That depends on a lot of factors: the culture and laws of where you live, the values and personalities of the individuals. But perhaps the two biggest factors are how much time has passed since the initial decision, and how the decision was initially framed. If you had a spur-of-the-moment Vegas wedding last week, that is probably easily reversed. If you’re twenty years into a marriage with children and joint property, it’s still possible to reverse the decision, but it’s much more difficult to do so.

Nonetheless, the framework provides a helpful heuristic, especially for getting out of analysis paralysis. If a decision feels reversible, probably best to choose a path and see what happens. Especially in a large organization, you’re almost certainly erring on the side of being too slow and risk averse.

Except.

Organizations often lack good mechanisms for undoing decisions. Once a decision has been made, a new status quo calcifies very quickly, and it can be surprisingly difficult to change course. It doesn’t matter how big or small the decision or even why it was made — the team will meet 2-3pm every Monday, we will eliminate the training budget, we will cater lunch on the last Friday of the month, everyone will work from home. In theory, it would be easy to reverse any one of those decisions; in practice, Shopify needed to have a bot delete 322,000 hours of recurring meetings from company calendars.

Organizational inertia is incredibly powerful. A decision might feel like a Type 2 decision, but once it’s been implemented, reversing it can be more challenging than you imagined. That doesn’t mean organizations continue on the same path forever. It means organizations tend to stay on the same path for too long, until there is some internal crisis or external force that requires a large-scale, capital-T transformation. Then a whole lot of decisions get made at once in a way that can be more destabilizing and less nuanced than if the organization could only figure out how to undo individual decisions more effectively.

Bringing a pilot mindset to decisions

Typically, pilots are smaller in scale, which makes undoing a decision less costly. But from the lens of reversibility, it’s perhaps more important that pilots define an endpoint. The endpoint creates an explicit opportunity to undo a decision or double-down on it. Piloting makes is clear to all the stakeholders that “undo” is a possible outcome. That makes us more willing to use metrics as a barometer for whether we should reverse a decision, and more open to changing our mind in the face of unexpected side effects.

Sample caption in relation to the image above which is very pretty - ohhhh (image credit: someone out there)

The trouble is that most organizations use the notion of pilots very narrowly. They reserve the concept for significant investments, often customer facing, always perceived as risky. But the notion of piloting can be applied much more broadly, as a mindset that is adopted for just about any decision made by any person in an organization.

Adopting a pilot mindset doesn’t have to be a big undertaking. To pilot a decision, all you really need is an end date: the appointment an organization has made with itself to revisit the decision and see how well it’s working. It’s great if you can define your criteria for success up-front and measure pro-actively. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with retrospective evaluation. What really matters is creating a shared understanding that the decision is being made for now, based on the information available, and we won’t hesitate to reverse course if different data emerges.

Creating an end date on a decision can be as simple as a hold in a calendar: “Decide whether we want to continue with X.” Once that mindset is pervasive, more of your organizations’ decisions will be genuine two-way doors. When decisions are more reversible, people will be able to make them more quickly and confidently, enabling the organization to be more nimble overall. As an added benefit, a pilot mindset inculcates more curiosity in your team. Instead of going into maintenance mode because a decision has been made, the team has a strong incentive to pay attention to the implementation, notice what is and isn’t working, and make adjustments as they go.

Enabling more nuanced reversal of decisions

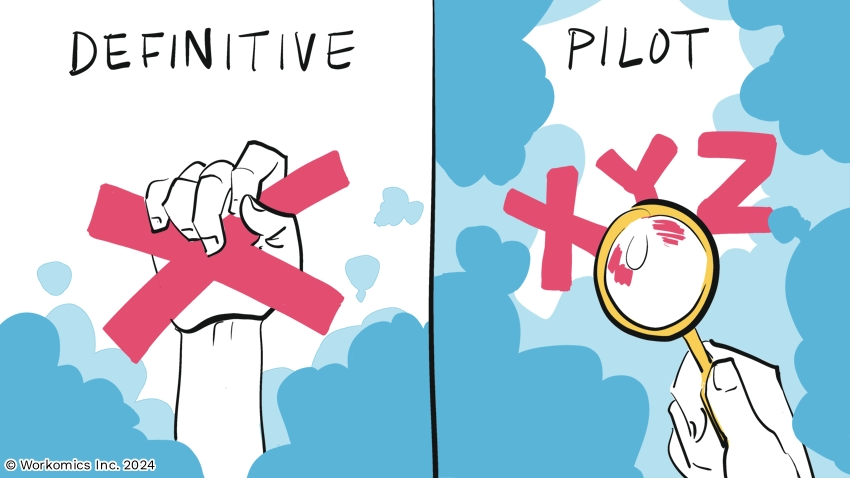

By contrast, a pilot mindset allows us be more selective and nuanced in how we undo decisions. We are able to tweak and adjust. Consider two different mindsets for a decision:

Definitive mindset:

We are launching initiative ABC to achieve outcome X.

Pilot mindset:

We are piloting initiative ABC. We’ll evaluate our decision at Time T by looking at measure X.

Now suppose Time T arrives, and the results for X are terrible. They weren’t your focus when you started, but you see that other results (Y and Z) are excellent. The data from ABC tell you that you can continue to achieve Y and Z with 30% of the original investment. The same data tell you that improving X might never happen, and would certainly take a lot more money.

What do you think happens in both cases?

Sample caption in relation to the image above which is very pretty - ohhhh (image credit: someone out there)

Well, this is a real example, where we saw an organization take a definitive mindset. When they got to time T, they continued with ABC, even though the results for X were well below expectation. Y and Z were valuable to the organization, but ABC was supposed to deliver X, so that’s where everyone focused. Then, some months later, ABC was axed entirely, and the organization lost out of the benefit of Y and Z.

We can’t know the counterfactual, but it feels likely that a pilot mindset would have changed the outcome. When they got to Time T, the organization might have been quicker to adjust the investment level and focus on Y and Z. The organization might have even viewed ABC as a qualified success and interpreted the poor outcomes with X as valuable learning. ABC could then have continued at a lower investment level for the foreseeable future, because Y and Z were both important outcomes for the company.

It’s a common refrain in organizations. We tell definitive stories about the decisions we make. We don’t want the decision to feel reversible. We crave certainty: about our resources and budgets, about our day-to-day activities, about how we’re contributing to the organization. If you’re not well-practiced at taking a pilot mindset, the ambiguity of a reversible decision feels uncomfortable. But that ambiguity is also a blessing. It allows everyone to stay curious about outcomes, and be more open to finding value from unexpected sources.

It’s a small thing, treating decisions as temporary and defining an end date. But the potential effect is outsized: more curiosity and experimentation, more two-way decisions, a more nimble organization. Certainly, it seems worth piloting for the next month or two. 😉

Our other ideas worth exploring

Asking for Help

The asymmetry of asking for help, autonomous vs. dependent help-seeking, and what it means for organizational effectiveness.

Podcast: Building Alignment with Co-Creation

Workomics appears on the Storylinking podcast. Susan Bartlett discusses building alignment with co-creation with host Tom Lietz.

Hierarchy, knowledge work, and gender equality

Flat hierarchy ismore effective for modern knowledge work, but recent research shows it might contribute to gender inequality