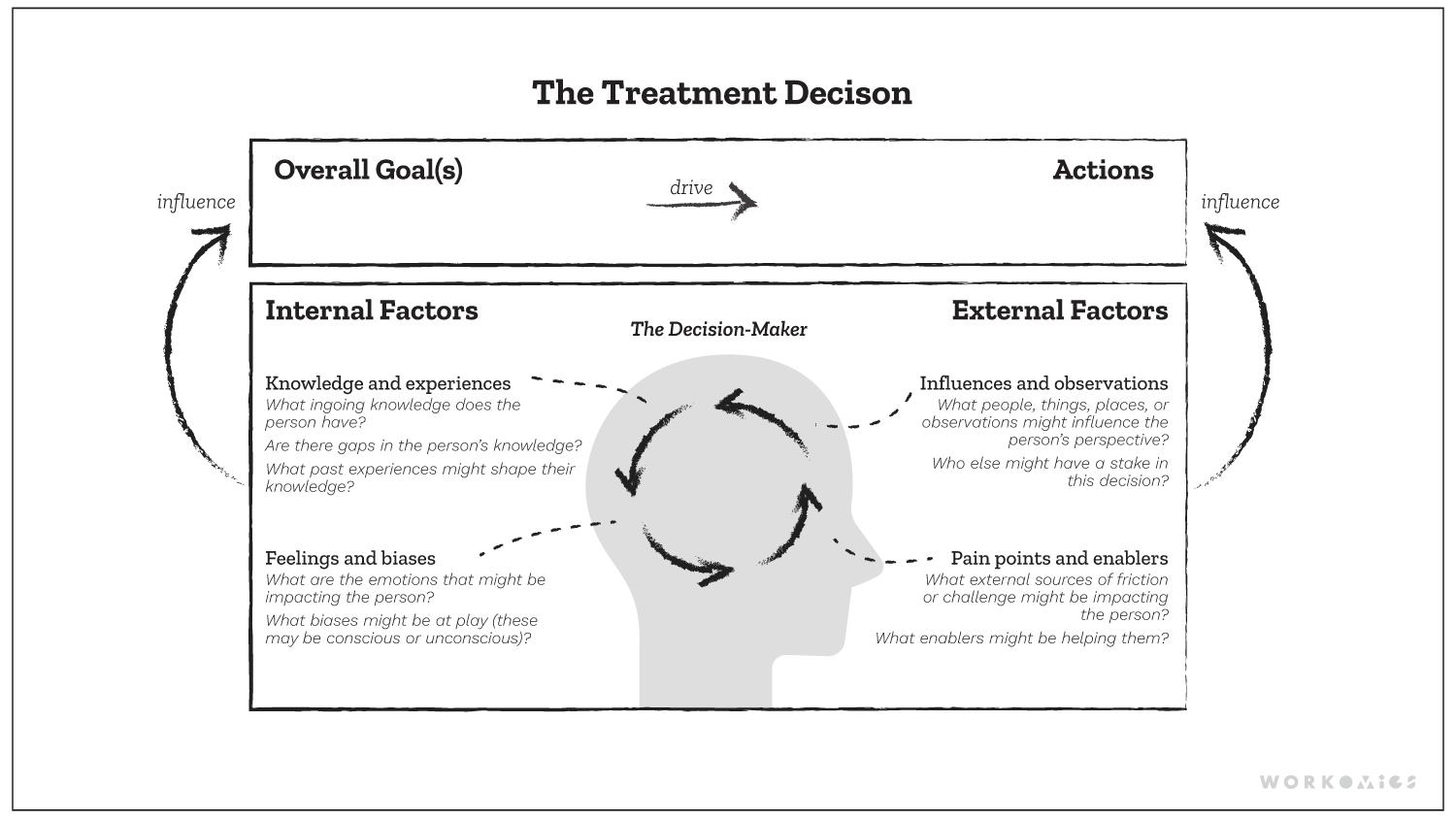

The Workomics treatment decision-making framework outlines key internal and external factors that shape prescribing behaviour.

Commercial pharmaceutical teams must build new strategies and tactics to drive business results when preparing for a new drug launch. The aim is to shape physicians’ treatment decision-making so that their product is prescribed to eligible patients. One key way to shape treatment decision-making is to make a product more salient to physicians’ goals, by grounding in the drug’s Phase III clinical trial data and indication. For example, an important goal might be “to give patients the best chance at survival” or “to give patients more manageable side effects.” Overall survival or time to relapse might become essential pillars in sales and marketing campaigns, as well as the frequency, severity, and ability to manage side effects.

But physician decision-making, particularly in areas of complex diseases like cancer, is complex! While building physician awareness and knowledge about a product’s label is very important, it’s not the only factor that might shape treatment decisions and prescribing behaviour. In fact, there are many additional factors outside of the product label that shape these complex decisions, and which, when also examined, may help us crystallize more holistic and effective go-to-market strategies.

Consider the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: Addressing physician confidence

A physician is seeking survival for their cancer patient. A newly-launched immunotherapy demonstrates overall survival in Phase III trials exceeding all incumbent therapies on the market. The product’s sales and marketing teams have effectively built awareness and knowledge of the product’s label and trial results among prescribers.

Nevertheless, a physician hesitates to prescribe the product. Why? Well, her peers have had mixed experiences with this new class of therapy. Her decision is influenced by her peers’ rocky first experiences, where they encountered challenges while learning to effectively manage immune-mediated side effects. She’s observed that her own nursing team is similarly inexperienced in this area, and in turn, she has internalized a bias surrounding their readiness to manage patients on this new therapy.

In this scenario, the commercial team has established awareness and belief in their product’s efficacy among prescribers. However, a better go-to-market strategy would include tactics to help nurses level up on immune-mediated side effects management and a focus on delivering better first-patient experiences to prescribers. Addressing this education gap effectively remedies an important barrier to adoption among HCPs and their clinical staff.

Scenario 2: Addressing practical barriers to access

A new cancer therapy has demonstrated meaningful survival outcomes for patients; however, to receive the treatment, the patient must be attended by a family caregiver throughout a lengthy hospital stay. The prescriber is a strong advocate for the treatment and they would like to offer it to their patient. The only trouble is the patient doesn’t have anyone they can call on to be their full-time caregiver during their hospital stay.

In this scenario, the patient’s lack of a caregiver is a barrier to treatment. Despite the physician’s preference and belief in the therapy, the physician prioritizes other treatment options that are “easier” for the patient to navigate alone. A more holistic go-to-market strategy would consider the real-world barriers and enablers that patients face while considering this specific modality in addition to physician awareness and belief in the treatment’s efficacy. For example, given that some patients might not have a caregiver, might the commercialization team find ways to amplify the work that third-party patient support organizations are already doing to help patients find volunteer caregivers?

Scenario 3: Navigating patients’ reluctance

In a clinical trial of an osteoporosis medication, patients had fewer severe bone fractures while on the product. A new formulation means that patients only need to take a tablet once a month. This drug has a similar side effects profile to other products in its class; common side effects are relatively benign, but the rare side effects are serious, including severe pain, problems with the jaw, and allergic reactions.

A physician wants to prescribe this product to his patient with osteoporosis. The patient leads a busy, on-the-go lifestyle, and the physician believes it will help her maintain her quality of life in the years to come. In the consult, the physician takes the time to explain the drug’s potential benefits and risks to his patient. He goes over side effects, both common and rare, and stresses how and when to take the tablet. The physician knows it’s essential for the patient to understand this important information, and he believes that the conversation prepared her to start taking the new medication safely, while feeling supported.

Meanwhile, the patient leaves the conversation feeling anxious and scared. To her, the side effects sound downright scary. The potential benefit — preventing fractures — feels abstract and hypothetical. She’s heard friends describe the drug as “caustic” and “unnatural.” She visits the product’s website, which shows old gray-haired ladies; women who do NOT look like her! She decides the drug isn’t for her.

In this scenario, the pharmaceutical organization didn’t adequately plan around the patient’s feelings and biases. An effective strategy would include patient education resources to help physicians explain important safety information to patients in a way that informs, not scares them.

Ultimately, treatment decision-making is complex, ambiguous, and varied. The most effective go-to-market strategies are simple, straightforward, and singular. Looking beyond treatment goals and product label helps build a more robust go-to-market strategy. Commercial pharmaceutical teams should examine their stakeholders’ influences and observations, barriers and enablers, feelings and biases surrounding the treatment. If they don’t, key tactics that can help drive business results may be overlooked. We think that only by grappling with the complexities and understanding the nuances will you be able to get to a strategy that shapes the prescriber’s overall goals and ultimately changes her prescribing actions. For this reason, the treatment decision factors framework can help organizations strategize more holistically, beyond the label and trial data.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Hybrid co-creation in pharma and biotech

Bringing internal participants together for a hybrid co-creation creates shared intentions and speed to market.

Informed Consent in Healthcare: Adding to FDA Guidance

We share best practices in patient communication that may help comply with FDA guidance on informed consent, as well as practical tips.

HCP Communication Best Practices

HCP communications from the pharma industry need to be more focused, trustworthy, and multipurpose, to deliver value in the clinical setting.