It’s curious that we have ascribed the (undeniable!) fatigue of remote work specifically to video meetings. In this post we’ll explore two theories as to why video meetings are more tiring—the scheduling and self-presentation hypotheses. While both are basically correct, they are also incomplete, because workdays involve so many things besides meetings. Is it really just the video calls leaving us all so tired?

The Scheduling Hypothesis

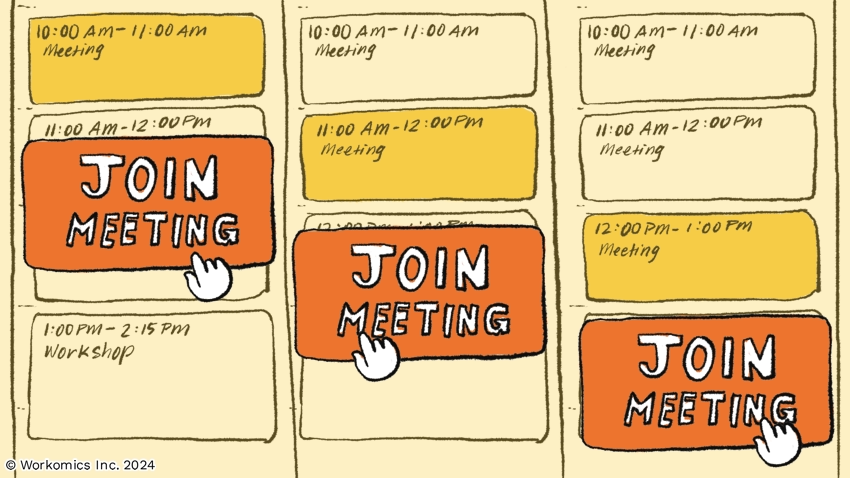

Earlier this year, Microsoft put out some interesting research around the effect of back-to-back meetings. They had volunteers participate in video meetings while hooked up to EEGs that monitored brain activity. On one day, they attended four back-to-back 30-minute meetings, while on the other they did ten minutes of app-facilitated meditation between meetings. The results showed that with the ten minutes of meditation, beta waves associated with stress did not build up over the course of the meetings. Ten-minute breaks also increased frontal alpha asymmetry, which is associated with being more engaged in meetings.

“Take breaks,” is good advice, but gosh is it hard to execute. There’s such a strong temptation to squeeze one more meeting into calendars, or to let the meeting run long because you don’t have a hard stop. Even when you succeed in keeping breaks in your calendar, it takes tremendous discipline to stop yourself from filling those ten minutes with emails or instant messages.

Rather than leave it up to individuals, it might be better to facilitate those breaks within the meetings themselves. If you are running an hour-long internal meeting, you can try to interrupt it halfway through: “Okay, everyone: mute buttons on, cameras off, and stand up and walk away from your computer and phone for the next x minutes.” Just as it’s easier to work hard in a group fitness class, group breaks can be easier to stick to.

The Self Presentation Hypothesis

Self presentation is the idea that most of us want to present a positive image of ourselves to the world; projecting this positive image takes significant mental energy. Video meetings heighten our self presentation efforts, partly because we can see our own image (at least by default), and partly because video meetings subject us to the eye gaze of others for much longer and at much closer range.

A recent study explored the self presentation hypothesis. Over a four-week period, workers were randomly assigned to keep their cameras off for the first two weeks and on for the second, or vice versa. Each day, study participants reported on how fatigued they felt. The researchers found that having cameras on for virtual meetings is more fatiguing, irrespective of the number or duration of the virtual meetings. The effect was more pronounced for women and for newer employees with less tenure in the organization.

The study also explored whether there were benefits in terms of feeling engaged or having voice in meetings. The results here were less clear-cut, but the additional fatigue from cameras on seemed to negatively affect both engagement and voice. But the researchers caution against over-generalizing these findings, since they studied the effects on the person turning the camera on or off, not the experiences of other individuals in the meetings.

There are clearly costs associated with having video meetings. For some meetings, those costs are completely worth it. For instance, the Design Thinking Zeal has a cameras-on policy that aligns with their goal of creating community, rather than just hosting a webinar series. In other instances, the best choice might be a one-on-one phone chat while both participants are walking — there is something incredibly rejuvenating in the combination of fresh air, exercise, and a voice-only conversation.

Contra the researchers in this study, the prescription is not as simple as individual flexibility on the choice of cameras on or off. Rather, we need to develop a discipline of thinking carefully about the kind of interaction we’re striving for, and whether cameras will add more than they detract. The end result should be cameras used by all attendees for only those meetings where the video adds an important dimension. For most people, that likely translates into video meetings a few times a week rather than a few times a day, and a corresponding reduction in fatigue.

Remote fatigue beyond virtual meetings

Dr. Cohen’s definition of “social support” is particularly instructive. It’s not just moral support (what Cohen calls “esteem support”). Rather, it’s specifically the combination of synchrony and the perception of actual resources available from your companions. To access social brawn, it’s not enough to have someone cheering you on — you need to feel like there is someone in lockstep who can jump in and provide tangible help.

When we’re working remotely, we lose social brawn from our colleagues. The lack of synchrony in remote work is obvious, but tangible help is also less available. It’s still possible for you to tap your remote colleagues for support, but it’s much more difficult. Because you’re working remotely, you and your colleagues don’t have the same “mutual awareness” of tasks or their context. It takes much more effort to communicate the required context when you’re not co-located.

What’s especially fascinating is that it’s not important whether you actually access that support from your colleagues. Being out of sync and knowing help from others isn’t easily available is a source of fatigue, in and of itself. Of course, Dr. Cohen’s empirical work is focused on exercise science, not cognitive work, and her lab does see large differences between individuals that require further study. However, her work suggests that even if we eliminated video meetings completely, remote work would still be more tiring. Organizations that work remotely need to have best practices for meetings, but they equally should think about how to solve for social isolation and mutual awareness of goals and contexts.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Mailbag: Social Change and Career Choice

In general, the more a job is focused on contributing to society and community, the less it pays. It’s not an immutable law of physics, but wages in the charitable sector consistently lag the private sector, and typically there’s a trade-off between doing good (for the world) and doing well (for yourself, financially.)

Three principles to make AI work for people and teams

Meet Daisy: An AI Case Study. Daisy is a Regional Sales Enablement Specialist for a large multinational in a heavily regulated industry. She works with sales executives in her region to help them build skills and deliver better outcomes for customers and the business.

An AI Policy-in-Progress

We use AI judiciously, so that we are minimizing the downsides and maximizing the benefit. Our use of AI should be additive, transparent, eco-conscious, and voluntary.