In 2024, Workomics sponsored Rotman Design Challenge. It was a six-week case competition, with teams of graduate students applying business design to tackle a future of work challenge:

Interconnected forces are shaping the future of knowledge work:

Remote/hybrid models are continuing to be tested and taking root

For the first time in history, five generations will be active in the workplace.

Employees are looking to forge a new compact with their workplace.

Against this backdrop, how might we help organizations actively create engaging, economically sustainable remote/hybrid work environments for today’s knowledge workers?

This post transcribes the keynote presentation Workomics delivered to open the final day of judging.

Let’s start by taking ourselves back in time, to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. A confluence of new technologies is emerging: new materials like iron and steel, new energy sources like steam engines, and new machinery like the spinning jenny. Together, they are fundamentally changing how we think about work. People are leaving agrarian life and heading to cities in unprecedented numbers. They stream into new workplaces and new jobs.

However, a lot of our social and cultural infrastructure is poorly equipped for this new industrial age. Whether it’s workers’ safety, living conditions, wages, or sanitation, the state of affairs generally ranges from awful to appalling.

But as the industrial revolution unfolds over decades, we will develop norms and institutions to better suit this emerging industrial world. Everything from publicly-funded schools to trade unions to the concept of a 2-day weekend will emerge during this era.

Which brings us to today. I don’t know whether our current era of remote work constitutes a paradigm shift on the order of the Industrial Revolution. But I do know this: it has all happened much, much faster.

For knowledge workers, our economy literally shifted to 100% remote work over the course of a weekend in March of 2020. It happened simultaneously, all around the world. We spent decades adapting the social fabric to better meet the needs of the industrializing economy; we’ve had four years since COVID-19 sent us all home. Given the speed, it should be no surprise that individuals, organizations, and society as a whole are still struggling to thrive in a new reality.

We are still living in a world optimized for most adults to congregate to work in central locations five days a week. Everything from how we fund public transportation to how we design our communities is maladapted for a world where many working-age people spend more waking hours at home than at any time since the 18th century.

An existential challenge to the employer-employee compact

For organizations that employ knowledge workers, I believe this era presents an existential challenge. Remote and hybrid work is only a catalyst that crystallizes other, slower-moving forces that have been unfolding for a long time.

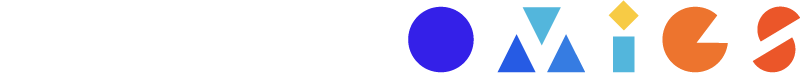

Traditionally, companies have offered a tradeoff to their knowledge workers: Give up a large measure of your autonomy and flexibility and in return, we will give you three things:

-

Stability

-

Structure

-

Resources to make you more productive.

Coming out of the Industrial Revolution, that was the fundamental bargain: come work here and you will have a stable income. We will give you structure, in the form of objectives and a ladder you can climb for promotions and raises. And finally, we will invest our capital in machinery and know-how so you can produce things that would be impossible on your own.

For today’s knowledge worker, does that still feel like a good deal?

Companies stopped offering stability in the 1980s when mass layoffs replaced jobs-for-life. Without stability, long-term career structure isn’t meaningful. Who cares about the career ladder if you’re unlikely to be around long enough to climb it?

More recently, remote and hybrid work have disrupted the day-to-day structure of work, such that it’s almost unrecognizable. If we’re not spending most of our days in the same physical spaces:

-

How do we coach and provide feedback?

-

How do we create camaraderie, transmit culture, and foster belonging?

-

How do we build collective, nuanced understanding of the complex strategies we’re executing?

-

How do we separate work time from personal time when everyone is constantly connected and working across time zones?

-

How do we keep our common humanity when we mostly see our colleagues as 2D boxes on a screen?

None of these questions is unanswerable, but to date, organizations haven’t found good answers.

Meanwhile, the value of capital has changed. Once upon a time, computers were mainframes only large companies could afford. Now, we all walk around with a powerful computer in our pockets. I don’t want to overstate the case — you can’t build a car without machinery and you can’t build Large Language Models without compute. But with a laptop and a few hundred dollars for software subscriptions, knowledge workers can access most of the resources they need to do their jobs. Their need for physical capital has diminished. Organizations still rely on human capital, but large companies need fewer and fewer workers to generate each dollar of revenue.

Given all these changes, it’s perhaps not surprising that knowledge workers are demanding a new deal. Why would they want to surrender their autonomy and flexibility when corporate offerings are so paltry? They want something different in return — something that goes beyond those stale old promises of stability, structure, and resources.

Companies need to bring a new compact to the table. Of course, that was the focus of the design challenge you’ve all worked so hard on these last six weeks. But it’s also something your generation of knowledge workers will have to continue to grapple with over the years ahead. You need to advocate for new bargains and experiment with new models.

But — just as the places we work have expanded, so too must our ambitions for improving work. Our Victorian forbears created schools, labour codes, townhouses, and weekly garbage collection. So too must we create the social institutions and cultural norms that will enable broad-based prosperity. Knowledge workers comprise only about 25% of the economy. The 75% of workers who can’t work at home in front of a laptop — they need a better bargain too.

For this challenge, knowledge work was the focus. But I hope you’ll take what you have learned and apply it more broadly, so that any new compact isn’t just for your own jobs and workplaces, but for society as a whole.

And with that, I’ll wish good luck to the students presenting today. We are looking forward to thinking alongside you and learning from you.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Mailbag: Social Change and Career Choice

In general, the more a job is focused on contributing to society and community, the less it pays. It’s not an immutable law of physics, but wages in the charitable sector consistently lag the private sector, and typically there’s a trade-off between doing good (for the world) and doing well (for yourself, financially.)

Three principles to make AI work for people and teams

Meet Daisy: An AI Case Study. Daisy is a Regional Sales Enablement Specialist for a large multinational in a heavily regulated industry. She works with sales executives in her region to help them build skills and deliver better outcomes for customers and the business.

An AI Policy-in-Progress

We use AI judiciously, so that we are minimizing the downsides and maximizing the benefit. Our use of AI should be additive, transparent, eco-conscious, and voluntary.