~M, Toronto.

Let’s start by saying the quiet part out loud: In general, the more a job is focused on contributing to society and community, the less it pays. It’s not an immutable law of physics, but wages in the charitable sector consistently lag the private sector, and typically there’s a trade-off between doing good (for the world) and doing well (for yourself, financially.) M’s question is really about how to think about that trade-off. Corinne Low is an economist at Wharton whose recent book Having It All gives us some helpful frameworks.

Social purpose and the disutility of labour

One concept Low talks about is the “disutility of labour.” Work is assumed to have a number of negatives or downsides (things that create “disutility” for you) — that’s what distinguishes work from leisure or hobbies. But the amount of disutility varies from job to job, and from person to person. If you really value social and community contributions, you’ll have lower disutility in a job that lets you make those kinds of contributions. It can be perfectly logical to give up some amount of salary to do work you find more meaningful.

However, Low would be quick to warn you against over-indexing on just that one element. The overall disutility of your labour is made up of many things: the commute, the predictability of hours, how much you like your colleagues. Every job is a package deal, and you should consider all the ways it will add and subtract disutility.

It’s also important to think carefully about the day–to-day experience of doing your job. Mission and purpose are important things, but tend to get lost in the humdrum of the day-to-day. Meanwhile, challenges like homelessness or climate change are wicked problems. You can expect wins to be few and far between and resources to be scarce relative to the scale of the tasks at hand. Your day-to-day experience might be dominated by frustration at the lack of progress against big, systemic challenges. You won’t get the same macro level sense of purpose from something like selling cellphone plans or opening bank accounts. But those jobs can carry a lot of day-to-day satisfaction at the micro level, as you help individuals and make their day a little bit better. This isn’t advice to go work for an evil company. But it is advice to weigh the actual satisfaction you will get from your actual work, not just the higher-level mission.

Squeezing out other contributions

If our social and community contributions are not coming from our jobs, then we are left with contributions outside of work. But the viability of that option is going to hinge rather crucially on how many hours are left after you clock out for the day. If, like M, you’re a knowledge worker who is fortunate enough to be able to weigh competing career options, chances are high that your work is “greedy,” and your hours are long. The more hours your job consumes, the less “outside of work” time you’ll have for other contributions.

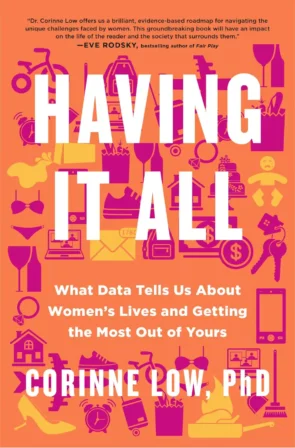

For M, the calculus is even tougher, thanks to something Low calls “The Squeeze.” Here is a chart from Low’s research into women’s time use over different periods in their lives:

Although individual women will go through the phases at different ages, the graph shows that for women with childcare responsibilities, there are three different eras. In two of them, the combination of childcare and household responsibilities is low enough that volunteering for social or community causes ‘outside of work,’ could be a reasonable plan, even with a greedy job. But in the middle era, which Low calls “The Squeeze,” the burden of housework and childcare increases substantially. In that season of life, a plan to make contributions to society alongside responsibilities at home and at work is much less realistic. There aren’t enough hours in the day.

Rethinking models for social contributions

M is far from an outlier. According to Deloitte, 9/10 of Gen Zs and millennials consider “purpose” to be important to their job satisfaction, whether that is through the work itself, or in how a job enables contributions elsewhere. Employers know this, which is why corporate volunteer programs are on the rise. The challenge with these corporate programs is that they tend to be shallow, episodic, or even self-interested. It’s hard to make meaningful contributions to thorny social challenges with just a handful of hours each quarter. The volunteer activities tend to be optimized for team cohesion and ease of logistics rather than true social impact. The causes are often picked for alignment with the corporate bottom line, rather than personal commitment to a cause.

For someone like M, the current state of corporate volunteer programs falls short of the real change she’d like to effect. How do we make space for sustained societal contributions when jobs are so greedy? Can we reimagine corporate volunteer programs to be more effective? We can perhaps take inspiration from service clubs, which brought together professionals from many different industries and firms to tackle really big things like the eradication of polio. What M needs — what all of us need — is a viable avenue to make meaningful and contributions to the causes we care about, in a way that can live alongside professional commitments, even when life is squeezed.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Three principles to make AI work for people and teams

Meet Daisy: An AI Case Study. Daisy is a Regional Sales Enablement Specialist for a large multinational in a heavily regulated industry. She works with sales executives in her region to help them build skills and deliver better outcomes for customers and the business.

An AI Policy-in-Progress

We use AI judiciously, so that we are minimizing the downsides and maximizing the benefit. Our use of AI should be additive, transparent, eco-conscious, and voluntary.

GenAI, capitalism, and human flourishing

How capitalism breaks down in the face of GenerativeAI, and why we need to find ways to optimize for human flourishing.