Ilana Ben-Ari is a toy designer and social entrepreneur. Her company, Twenty One Toys believes that the skills we need for the future of work are the ones we were amazing at in kindergarten, until the academic school system taught us to not use them. Her mission is to design toys that put play on the agenda, in both the classroom and the boardroom.

Ilana is one of our clients here at Workomics, and we’re also an enthusiastic customer of her corporate workshops. We especially like the Failure Toy workshop as a way of building trust and rapport within newly-formed teams. It helps people get comfortable with being vulnerable and taking risks together in a really short period of time.

In this interview, Ilana talks about how she turned a toy into a company, and how feelings and empathy intersect with business and leadership.

Workomics: Twenty One Toys turned ten years old in 2022, but the Empathy Toy is even older than that. I’d love for you to walk me through some of those early years and how a toy became a business and your job.

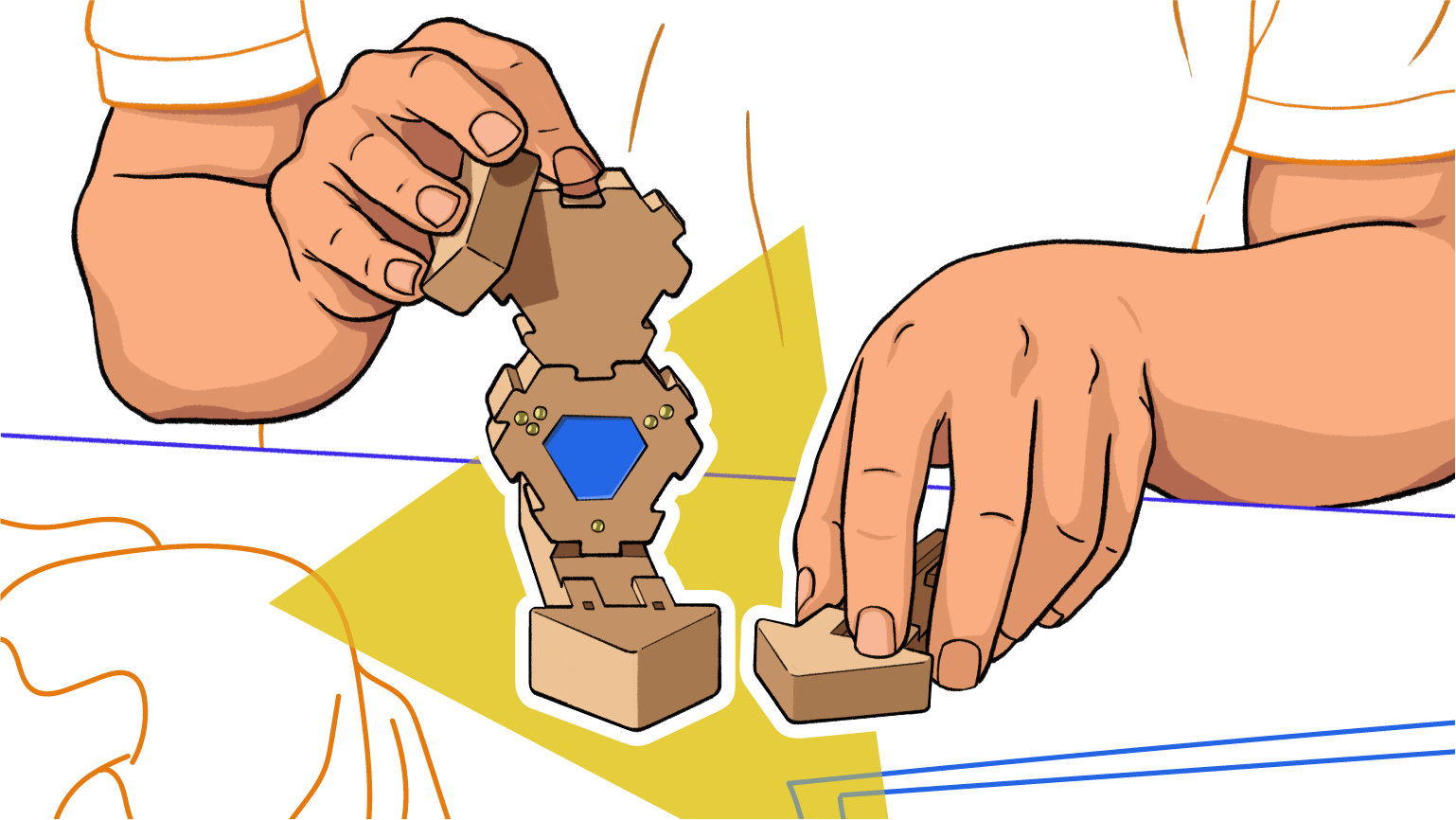

Ilana Ben-Ari: I designed the Empathy Toy in 2006 as my thesis project in university. I’ve given a TEDx talk on the origin story, but I was matched with the Canadian National Institute for the Blind for a year-long project to design a navigational aid for the visually impaired community. I had two months to do research and I was a bit shameless with trying to connect to as many people as possible. I ended up spending two months speaking to adults and kids who were born with or developed visual impairment.

The one thing you learn in design is you need to shadow someone and observe them, not just interview them. You’ll ask, “hey, what are your challenges,” and people say, “I’m fine.” But then you watch them and you realize, “Well, you’re fine because you’ve adapted and you’re very resilient, but maybe you shouldn’t be dealing with this.” I think that’s what I love about the design process. You have to be humble, open, interested and at the same time a little pushy.

All that research led to the conclusion that my navigational aid would be a toy or puzzle. I would test it during the day in a classroom with a visually-impaired fourth-grade student and her sighted classmates. Then I would test it again at night with the sighted university students in my studio. That’s when I started to realize the toy was just as challenging and rewarding for multiple ages and abilities.

WKO: You have a toy and a thesis project for university. And then six years later, you have a business.

IBA: The Empathy Toy ended up winning a very prestigious design award: best-in-show out of all of the design grads in Ontario. My professors were very excited and really encouraged me to find a company to manufacture and sell the toy. The idea of me starting my own business was so beyond anybody’s imagination; no-one thought that was the route. Luckily, there wasn’t a company that was interested in taking the Empathy Toy and manufacturing it, so I moved to Montreal, worked in lighting design, and just kind of shelved it.

Then I had a moment where I was watching Sir Ken Robinson’s TED talk on how schools kill creativity and I was screaming at the computer in recognition. In that moment I knew I wanted to start a toy company. The empathy toy would be the first toy, but I wanted to design an entire suite of toys that teach the kinds of creativity skills in Ken Robinson’s talk. I thought I had it in me to design more than just one toy. Game design has always been my passion. It’s such a beautiful mix of physical products, art, philosophy, and human behaviour.

I don’t think anyone thought it would work. That was an amazing gift because there wasn’t any fear of not living up to expectations; there were no rules. I built the business through a series of escalating dares: tell people you’re going to start a toy company, apply to this artist grant, get the website going, learn how to code, start going to conferences, make prototypes.

I would just sneak into education conferences and leave a prototype on a table. Teachers would flock and start asking, “Who left this here? What is this?” And I just approached it more like a designer than a typical businessperson — go straight to the source and validate that people want this.

Then an education consultant saw the toy at one of the conferences and sent my Twitter to a school board. Next thing I know I get a phone call and they’re putting in a five-figure order based off a TEDx talk and a prototype. And not only did I make that sale but I told them to pay me upfront in full and it would be ready in four months. Then I just had to go find a factory. I didn’t start calling myself an entrepreneur until at least two years in.

WKO:It’s interesting that you juxtapose ‘designer’ and ‘entrepreneur,’ almost as opposites. Why do you think it took you so long to call yourself an entrepreneur?

IBA: I think you have to be very, very open in mind and spirit to do the work of creating. But if you do that without creating healthy boundaries, it can be problematic. I had someone show up who convinced me I was “just” the designer, and not a businessperson. This person said, “I can write a better business plan than you. My words are better. I’m the smart businessperson.” And I said, “Sure whatever. Let’s go. I just want this to exist.” I gave away my power immediately and dismissed the fact that I invented the toy, started the business, created the brand, told the story, and got those sales.

That went on for a couple of years, until I finally removed that individual. At that point we were six figures in debt with no sales coming in. It was dark days. But within a month of having that person leave, we —I— made another five-figure sale. And then I realized, “Oh, wait I actually can run this business. I’m a much better salesperson and marketing and business development person than I give myself credit for.” There’s still so much I’m learning but I think I gained my confidence and proved to myself that I am capable and allowed. It took me a long time, but I think removing that person was when I got my entrepreneur badge

WKO: Is the business side of 21st century skills is something you’ve been percolating.

IBA: I know what the next seven toys are. I have already made Empathy Toy and Failure Toy and the third one that I’ll be inventing next is the Improv Toy. I truly believe those are the three core skills you need to create something or invent something.

The next three after that are all about value. The first one will be around negotiation. Compared to winner takes all, negotiation is so much more interesting. The second one will be about rule breaking. Different people can get away with breaking different rules. It seems that the best entrepreneurs know when to break the rules a little bit. The toy will be exploring rules and how rules are created. The third one will be about decision making which is so exciting, because I literally have to make 50 decisions a day. And with decision-making you touch on leadership and you touch on democracy. Negotiation, rule-breaking, and decision-making: I think those three are just going to be so rich and those are the classes and the lessons I wish I had gotten before I started with this business. I’m learning the school of hard knocks version of it.

The final one is very near and dear to my heart, which has to do with cross-cultural dialogue. That will be the last toy—the biggest and hardest one, too.

WKO: I know scale is something that’s on your mind these days, in large part so you can carve out the time to design those new toys.

IBA: In the early days, I didn’t want the risk of investors and spending time convincing them how successful this would be and then being beholden to them. So instead of taking that risk, I took a risk with my own mental health. “I’ll just be poor and work until midnight.” We had a lot of external success, but financially we were in a really tight spot. I lived off $500 a month by living with seven people and AirBNB-ing my bedroom. I never designed the business with my health at the centre. Why would I? I designed it with the impact of the toy at the centre. So all the decisions I made were what is best for the toy and then what is best for the collective.

It’s not a successful business to me if we’re profitable, making impact, our toys are beautiful, everyone’s giving us press and awards, but I am personally working until three in the morning every day and I don’t like my job because I’m not designing toys.

I was very lucky at the beginning. I found a market right away. I was able to prove impact. We won awards from the Mayor of Winnipeg for how the toys have helped reduce bullying in schools. I know the toys work in that space and in the corporate facilitator space. I’ve proved my point. There is a place for toys. There is a business case for this and a real social benefit from this.

I’m the most excited I’ve ever been about the future of the company because now I really understand the financial elements of the business. I really, really get it, more so than before. Where I get most excited is building an engine that I have influenced, and where I am needed but not necessary. One of the metaphors I would use is with the Improv Toy. The elements of improv are not just throwing spaghetti at a wall. It has very clear rules and structures. Once those are grounded, then you can play. Before you can jump around and mix it up, you need a really solid ground to be creative.

With the business overall, I feel like I’m at that stage where I’m almost, almost on the solid ground so I can go back to living in my creative space. That has been my motivation: to get back to being a designer, not in the absence of being a businessperson, but having a structure so I can live in both of those worlds.

WKO: Was COVID a setback for that objective?

IBA: In 2020, we were finally in the financial position where I thought we could level up. Then when COVID hit, we lost 95% of our revenue. On the other hand, working remotely has opened up this world of possibilities. From a leadership perspective, going remote was one of the best gifts I’ve received. I was not able to grow into the leader I needed to be when I was in-person in the office. Being remote has made it possible for me to be in a team meeting and then I can just turn off my computer and go for a walk and have emotions and feelings without feeling like I have to hide my emotions because I’m in the physical presence of my team.

For me, I think what makes me a great designer is that I’m overly sensitive to other people’s emotions. When I’m designing a toy, it’s great — even if someone isn’t telling me how they’re experiencing the toy, I can see it. But it goes from a superpower to a shadow when I’m in a leadership role — if I’m making an announcement and I can tell that people do not like that announcement.

Those are tensions I found very, very difficult to navigate when I was sharing a physical space with my team. When it’s remote, I can show up with more clarity and decisiveness. And then I can get off the Zoom call and think about all the ways that I’m not so sure about this.

However, I do think from an employee’s point-of-view they’ve lost a lot from not sharing a space. Selfishly, I’ve benefitted tremendously from a leadership and efficiency perspective. For the team, their quality of life and connection to the mission and the business would be much stronger if they were sharing a physical space.

WKO: Relationships and connection are so critical to the kind of work that you do.

IBA: I find there is a tension there because I want to show up as human and as myself in every interaction. What I’ve learned is that it can be a version of me, because I’m an open book and I tend to overshare. I want to design a business that lets me collaborate in a way that’s win-win for everybody.

I love working. I truly enjoy having a really rich challenge and working with others on it. I want to be able to work with people that I enjoy working with. A lot of that has happened organically, but I think I’m in a moment in time where we can reset and I can set up new ways we can all work and play together.

Our other ideas worth exploring

A business in transition

Rebecca Chan, owner and creative director of Rebecca Chan Events, talks about transitioning her business from weddings to corporate marketing.

Investing for long-term sustainability

Joelle Faulkner, CEO and Founder of Area One Farms, talks about building up her own investment firm, focusing on Canadian agriculture.

Fostering connection, community, and care

Jill Curran, owner of two tourism-based businesses, talks about building layers of care and community into clients’ travel experiences.