Hierarchy has an uneasy status in the current cultural moment. It feels trendy to eschew hierarchy: companies increasingly trumpet their flat structures as a feature in job ads (1). Even so, hierarchy remains a pervasive default — a “taken-for-granted belief in managerial power as the primary mechanism for ensuring performance.” (2)

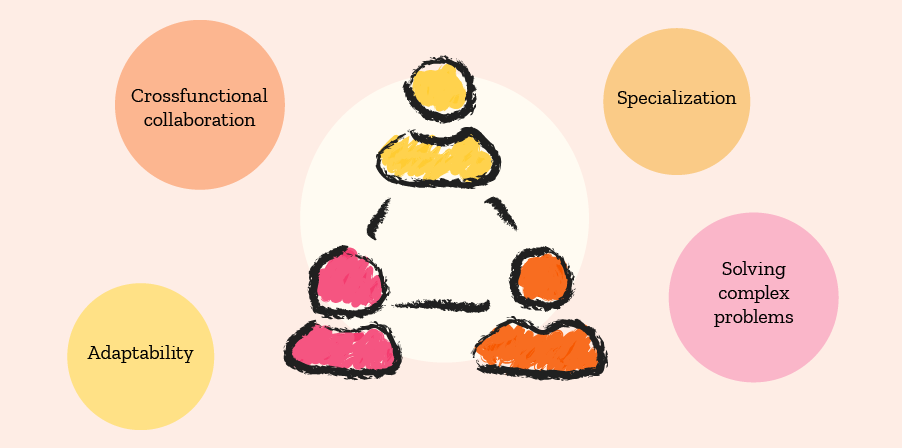

Hierarchy has its merits. A fairly robust academic literature shows hierarchy is very good at clarifying roles and responsibilities to enable reliable execution of known tasks in stable environments. That same literature finds hierarchy is less effective when teams need to:

- solve complex, non-routine problems

- collaborate across functional boundaries

- adapt to changing conditions

- apply specialized, intensive knowledge to execute the work.

Those four characteristics are, of course, the defining features of modern knowledge work, so you can see why organizations increasingly tend towards flatter structures over taller ones.

That doesn’t make flat structures an unalloyed good. In the study of flat hierarchies in job ads, Hurst, Lee, and Frake (2024) discovered that women are less likely to apply for jobs that tout a flat hierarchy in the job description. When they unpacked the reasons why, women cited three main reasons for preferring more hierarchy:

- More hierarchy offers more opportunity for promotion and career advancement

- Less hierarchy burdens them with more work

- Less hierarchy makes it more difficult to fit in.

Hurst, Lee, and Frake don’t suggest that a flat organizational structure is automatically problematic. However, their findings do suggest that we can’t just throw out hierarchy without carefully considering what will take its place. Given that hierarchy is less effective for modern knowledge work, how might we design flatter structures that avoid negative unintended consequences?

Hierarchy at Workomics

Workomics is what Lee and Edmondson (2017) define as a self-managing organization (or SMO):

-

Workomics has no reporting relationships whatsoever, such that, “the notion of ‘reporting’ to someone who has ‘authority over’ you becomes anathema.”

-

While not formally defined, Workomics employees hold decision rights that, “cannot be superseded by someone simply because s/he is the ‘boss.’”

-

Project teams at Workomics are free to organize as they see fit — that is, “the work group, rather than the individual, is the essential unit of work, and control is exercised internally by group members.”

Workomics has a flat structure because that makes us better at the key elements of knowledge work — solving complex problems, collaborating cross-functionally, adapting to change, applying specialist knowledge. However, we are also a firm that is predominantly women, so we thought it would be interesting to unpack how our approach to flat hierarchy attenuates— we think — many of the equity challenges that can arise in a flatter structure.

Lee and Edmondson’s research provides a helpful framework for understanding how we have designed our own (lack of) hierarchy. Across different domains, they categorize SMOs based on the degree of centralization — that is, the degree to which things are determined by a single “boss” figure vs determined by individuals doing the work. The six domains are:

- Work execution

- Managing and monitoring work

- Design of the organization and the work

- Allocation of work and resources

- Management of personnel and performance

- Firm strategy.

Lee and Edmondson draw a distinction between SMOs and organizations that strive to be “less” hierarchical or flatter while still maintaining managerial authority and reporting relationships. In those organizations, only the execution of work is decentralized, and partially so. By comparison, in true SMOs, multiple domains are partially or fully decentralized.

Our hypothesis is that decentralizing only work execution is a primary source of equity concerns that make women (3) less likely to apply to flat org structures. Consider:

- In the absence of hierarchy, organizations might fall back on more patriarchal norms, making it more difficult for women to exert influence or have their voices heard.

- If work is not managed within the strictures of hierarchy, women may find they are stuck with more of the workplace’s “invisible labour.”

- Without a hierarchy to create seats at the table based on role, participation might rely on “old boys’ networks” from which women feel excluded.

- Without formal hierarchy, women might find their contributions less likely to be recognized.

If our hypothesis is correct, then decentralization of other domains at work is important for creating org structures that are both flat and equitable. In the case of Workomics, we think there are three domains where our choices to decentralize (or not) have made a big difference.

How We Design the Organization and the Work

As is common in small companies, the organization and the work is designed around individuals’ interests, aptitudes, and bandwidth. These are mutually understood at a very fine-grained level, so people are working with their superpowers most of the time. The challenge is that individualized approach to organizational and work design often comes with an implicit hierarchy.

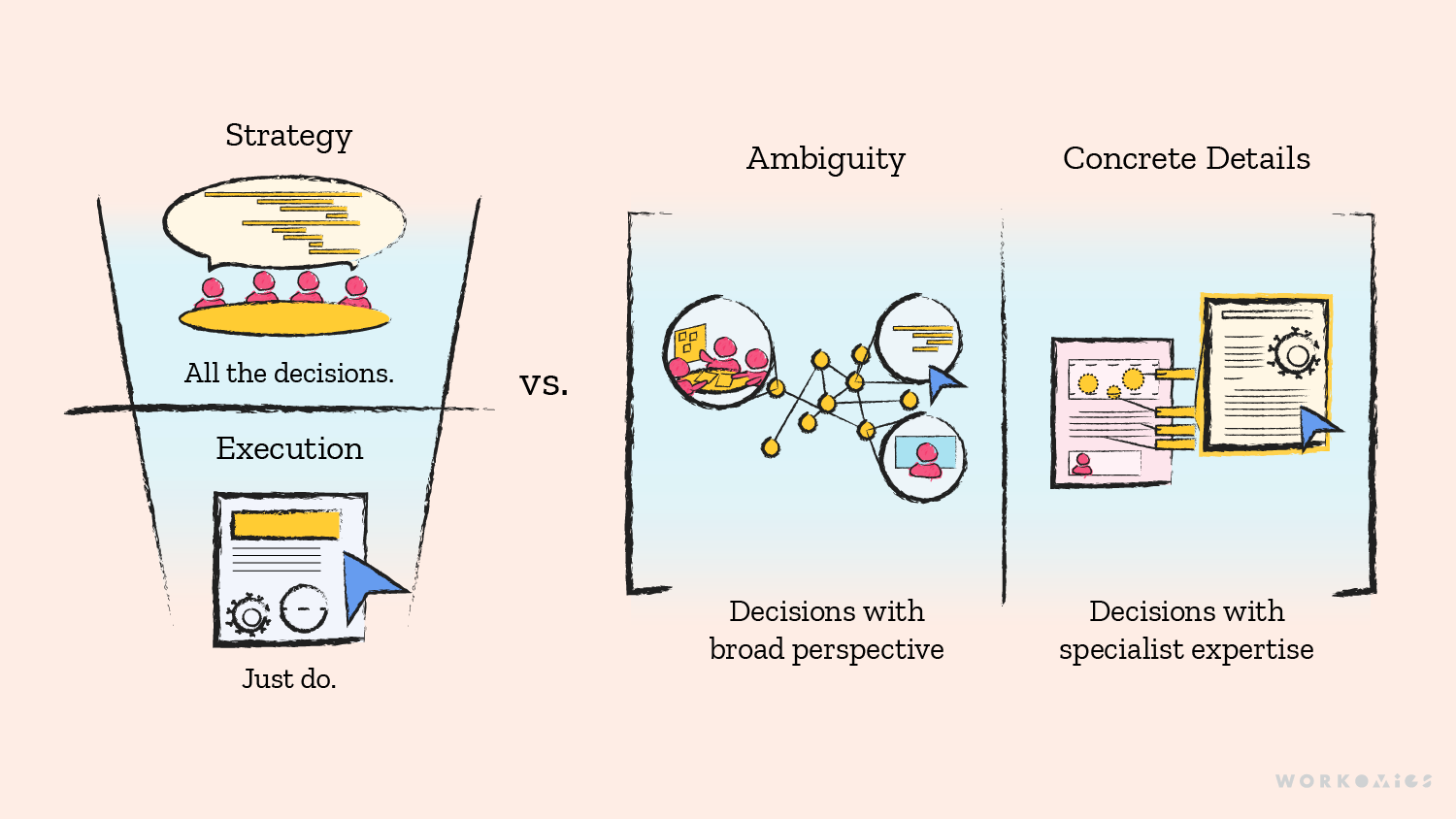

The twentieth century capitalist model tends to devalue the work of people who execute, relative to the people who set goals, make plans, and direct the work. When that model emerged, a lot of execution work was repetitive and low-skilled. But in modern knowledge work, what we think of as “execution” is complex and ambiguous. The folks who do the goal-setting and plan-making are often lacking the specialized and intensive knowledge needed for successful execution. And yet, even when organizations lack formal hierarchy, they tend to default to an informal hierarchy, where the work of setting goals and making plans is somehow “more than” the work of carrying out those plans.

At Workomics, we make a conscious effort to value work differently, and prize execution in particular. There are individuals who contribute best by working in ambiguous concepts, making decisions that draw on broader perspectives and connect dots. There are individuals who contribute best by working on tangible deliverables, making decisions that draw on deep, specialist knowledge and elucidate details. The relationship between these two ways of working is deeply symbiotic: each serves the other, making them more effective.

We strive to value them both equally in the organization — in terms of financial compensation, but also by creating a culture where everyone shows deference to the expertise of doing the work.

How We Allocate Work and Resources

At Workomics, allocating work and resources is the only domain that is fully centralized — the decision to take on a project or a client is not made collectively. Someone thinks carefully about what the organization wants to achieve; what we have the capacity to take on; how many people (and which people) should be assigned; the approximate size and shape of the work.

Organizationally, someone is in charge of defining “enough” — enough resources, enough revenue, enough ambition. Importantly, “enough” is a two-sided concept — most organizations are clear on what “too little” means, and so are we. But we are equally dogmatic about “too much.”

That’s because knowledge work is practically infinite. If you are in the business of making widgets, you reach a point where the widget is made and you are done. In the knowledge economy, “done” is elusive — there is always something you could add or improve. If you do knowledge work in a non-hierarchical organization without a guardian of “enough,” workloads can grow uncontrollably.

We have centralized the allocating (and re-allocating) of work and resources, making sure there is enough for the job at hand, and determining when enough has been done.

How We Do Personnel and Performance Management

To the extent there is performance management at Workomics, it is decentralized and informal. There is no career ladder to climb, and everyone joins the team understanding that.

Workomics is, however, still a company with owners. There are people who get to decide whether employees will continue to draw their paycheques. That kind of power imbalance fundamentally creates hierarchy, no matter how much you decentralize any other decision rights.

One way we address that power imbalance is through transparency on termination. In employment contracts, we specify how much working notice and severance employees will receive. In team meetings we discuss things like runway and operating capital, so employees know what to expect for the months ahead. These steps mitigate some of the effect of the power imbalance, but the imbalance itself remains.

However, we believe that the nature of knowledge work actually reduces the power imbalance. Managerial authority is classically described as “irrevocable from below,” as if the workers have no other viable option. In a capital-intensive industrial assembly line that was perhaps the case. But modern knowledge workers are highly-skilled individuals. In our case, they are charged with self-managing their own work. Any one of them could easily ply their trade elsewhere, and thereby revoke managerial authority.

In modern knowledge work, the more apt classical phrase is “consent of the governed,” meaning that workers who are subjected to rules have the power to agree or disagree with them. As long as there is a traditional shareholder structure, the managerial work of making decisions — especially hard ones about people’s livelihoods — still has to happen. But if the legitimacy to make those decisions only exists as long as employees are consenting to the model, then hierarchy shifts to a more balanced power dynamic.

Workomics is a small firm, doing particular kinds of work, so there are limits to what can be generalized from our model. However, we do think that our choices around decentralization help allay the specific concerns Hurst, Lee, and Frake uncovered in their research.

-

Because we highly value execution work, even over managerial work, it is easier for employees to feel like they “fit in.” Their unique skills are valued for what they are, and we are not asking people to map themselves into a broader organizational model.

-

Because we have fully centralized allocation of work and resources, people don’t have to worry about overwhelming workloads. There are sometimes still too-busy weeks, of course (allocation is rarely perfect). But over the long-run, workloads are in a sustainable equilibrium.

-

Because we don’t have promotions at all, there is no concern that things like pay increases and title changes might be handed out capriciously. Because we operate from the principle of “consent of the governed,” there is a more balanced power dynamic, even in the domain of hiring and firing decisions.

- Hurst, Lee, and Frake (2024). “The effect of flatter hierarchy on applicant pool gender diversity: Evidence from Experiments.” In 2010, about 13% of job ads mentioned the company’s flat hierarchy, but by 2019, that had grown to about 23%.

- Lee and Edmondson (2017). “Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing.”

- Hurst, Lee, and Frake’s research focused specifically on gender, but many of these factors would apply equally or more so for visible minorities.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Mailbag: Social Change and Career Choice

In general, the more a job is focused on contributing to society and community, the less it pays. It’s not an immutable law of physics, but wages in the charitable sector consistently lag the private sector, and typically there’s a trade-off between doing good (for the world) and doing well (for yourself, financially.)

Three principles to make AI work for people and teams

Meet Daisy: An AI Case Study. Daisy is a Regional Sales Enablement Specialist for a large multinational in a heavily regulated industry. She works with sales executives in her region to help them build skills and deliver better outcomes for customers and the business.

An AI Policy-in-Progress

We use AI judiciously, so that we are minimizing the downsides and maximizing the benefit. Our use of AI should be additive, transparent, eco-conscious, and voluntary.