September’s Internet water-cooler was buzzing about Paul Graham’s essay on Founder Mode. Graham’s essay says there are two ways to run a company: Manager Mode and Founder Mode. Manager Mode is for “mere” professional managers, where the chief executive “tells direct reports what to do, and it’s up to them to figure out how.” Getting more involved in that is micromanaging, and therefore bad.

But founders are different — they can unlock Founder Mode, which Graham believes is a better way to run a company. In Founder Mode, you pick and choose key areas of day-to-day operations to be super involved in.

Graham describes Founder Mode and Manager Mode as “two different ways to run a company.” Even though Founder Mode is clearly superior, it’s poorly understood and “business schools don’t know it exists.” Instead, “everyone” says that Manager Mode is the only way go. You have to “hire good people and give them room to do their jobs.”

But in fact, only Manager Mode is about running a company. Founder Mode is about something very different: growing a company far beyond its current scale. Many companies successfully operate in Manager Mode, because they are at a stable equilibrium, staying about the same size and scope. Once you try to scale a company, the game changes, and every company runs up against the same immutable law of physics: time is finite.

Unless you’re building time machines or clones, no founder ever has more than 8,734 hours in a year. As the company grows, the work required to run the company will eventually exceed the founder’s capacity to do it. Inevitably, founders must delegate details to others, including the details of some important things. The only questions are what to delegate, to whom, and how.

The trouble with Manager Mode

For BigCorp Inc., a company in a stable equilibrium, Manager Mode works reasonably well. “the way we do things around here” is something that already exists — in documentation, norms, processes, precedent, institutional memory. In that environment, it makes a lot of sense for a CEO to hire a strong executive and give her room to do her job. Her peers and her team can fill in the gaps.

The problem with “hire good people and give them room to do their job” is that it’s describing the goal-state, not advising how to get there. It’s like telling an infant they should learn to ride a bike in order to get around faster — Not wrong per se, but unhelpful for the current developmental stage.

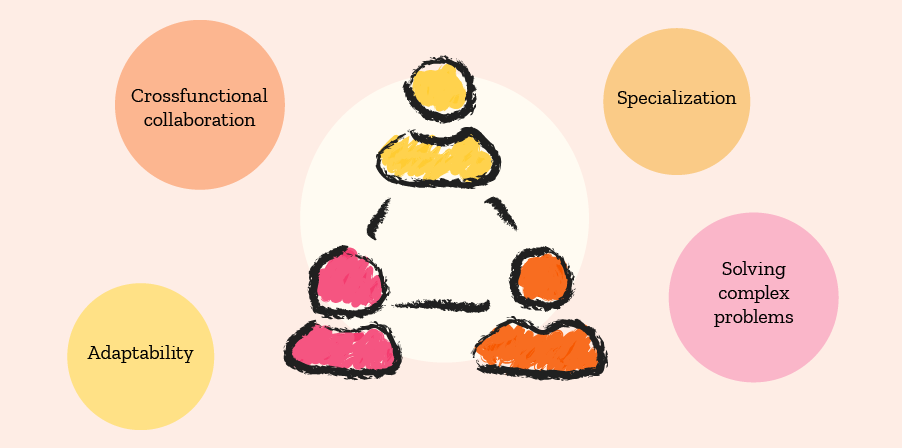

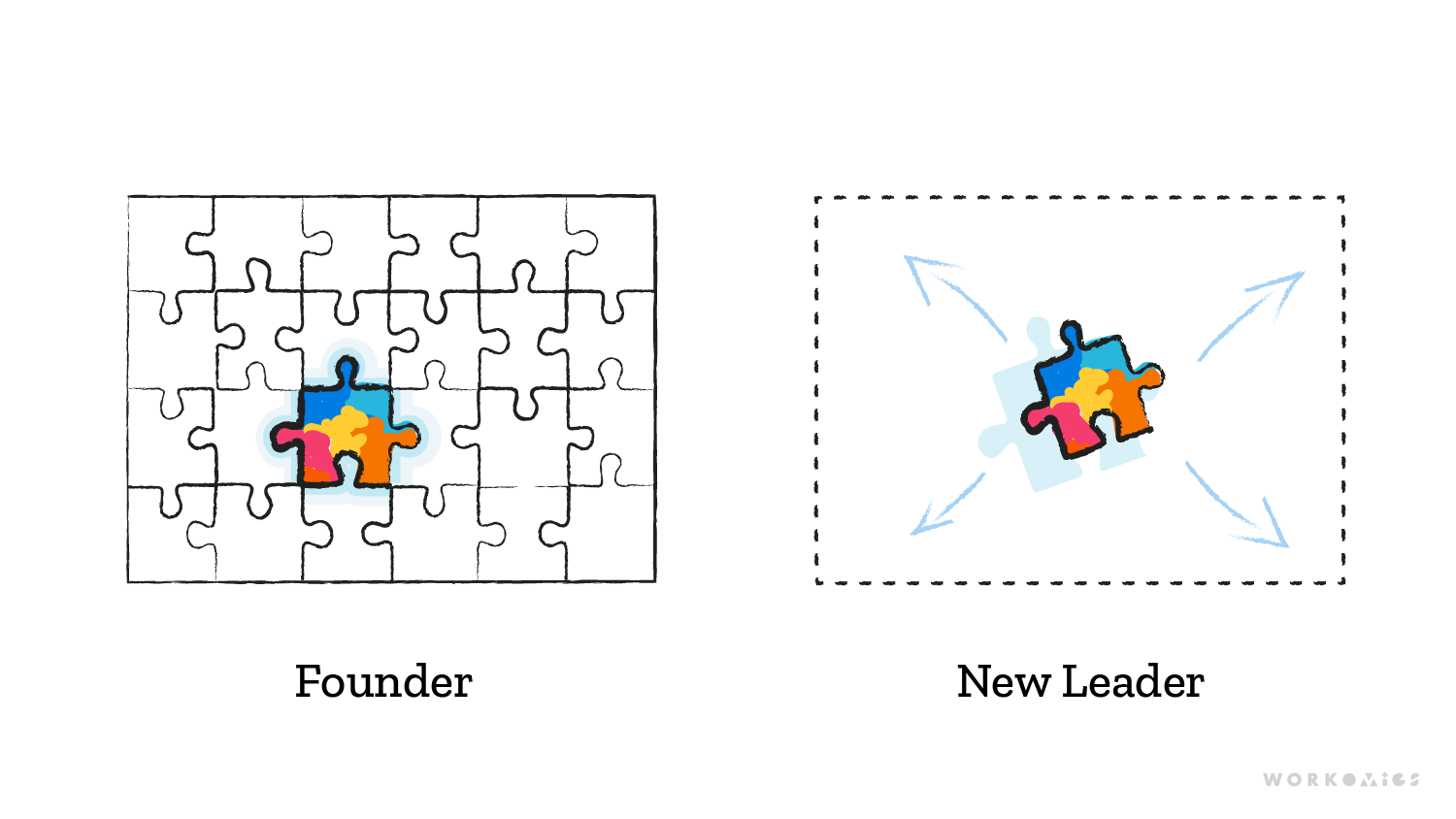

When a senior person is hired to run part of a scaling start-up, that function will be completely transformed. You are taking what used to be a piece of the founder’s job, handing it to someone else, and saying “please turn this into a job in its own right,” or even, “please turn this into a whole team or department.”

Suppose the founder is hiring someone to be head of marketing. When it was part of the founder’s job, “marketing” was necessarily constrained by all other the tasks on the founder’s plate. Now, marketing has become the sole focus of someone else, so the scope of marketing can and should expand. But there are infinite ways that could happen. The new leader not only brings all their preconceptions and past experience to the role, they are missing all the puzzle pieces that the founder has. Left to their own devices, the new leader is highly unlikely to design a marketing function that aligns with the founder’s (and the organization’s) big picture.

Now imagine the founder attempts to scale using Manager Mode: she will be handing out lots of puzzle pieces all at once, to different people. Where once she had a puzzle where all the pieces fit together, very quickly there is a bunch of different disconnected chunks, and no obvious way to put them together into a coherent picture.

Manager Mode is not a switch to flip, but rather the result of a gradual evolution. It’s what a company looks like after it has done the hard work of scaling, not what a company should look like while it is in the throes of growth.

A Founder Mode Hypothesis

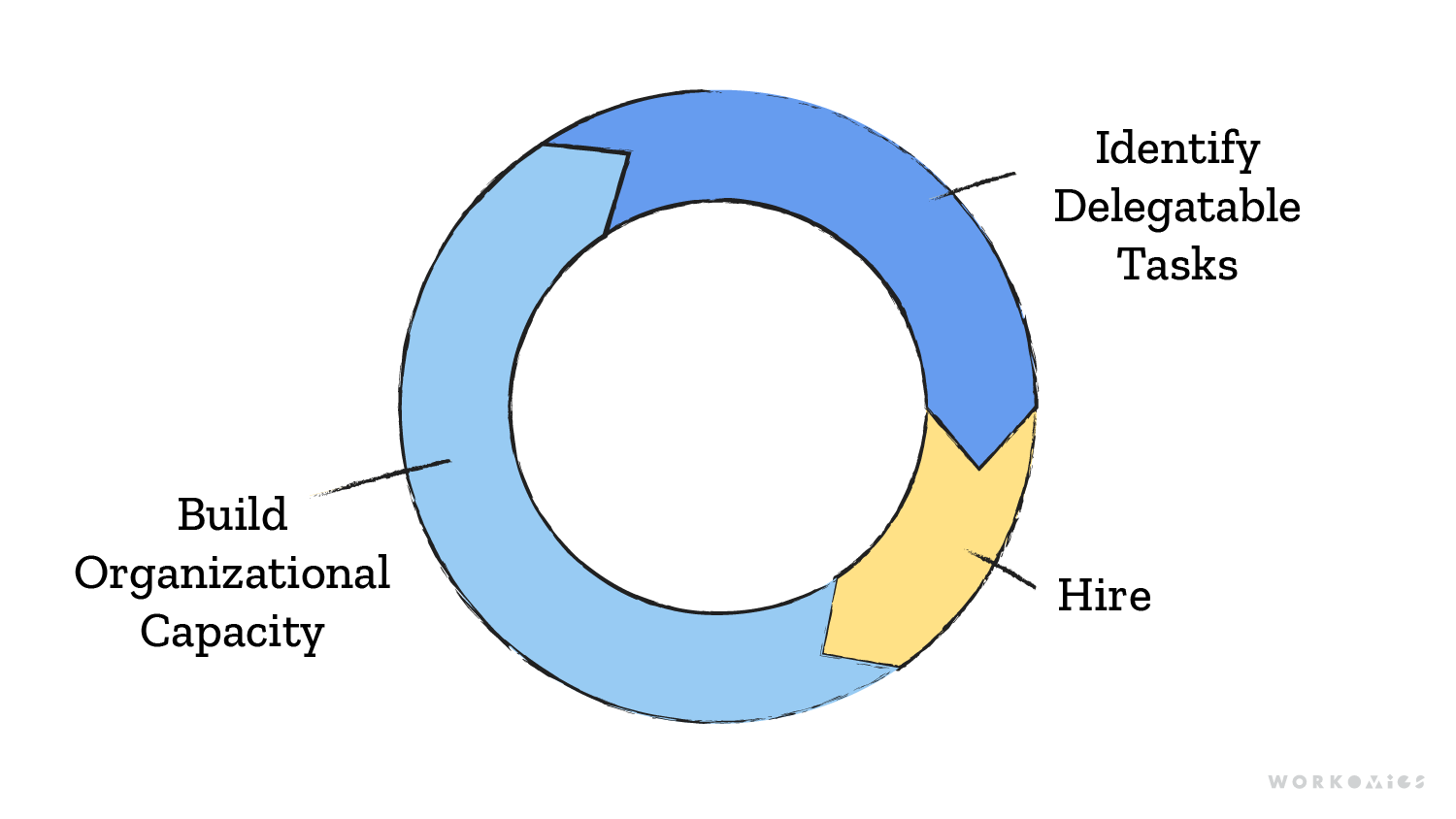

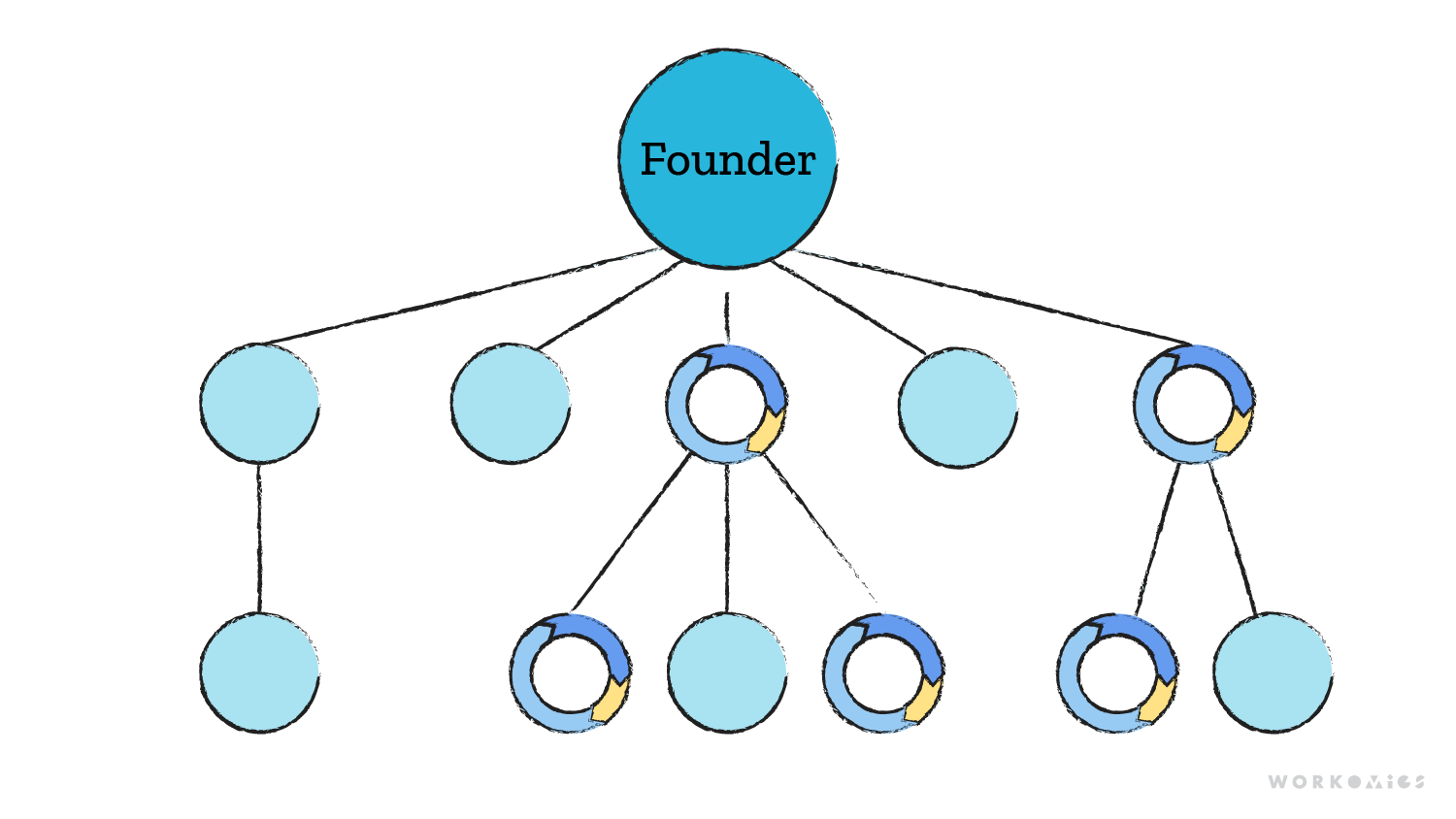

If Founder Mode is the process of scaling, what does that look like? Here’s a hypothesis: In its most atomic form, Founder Mode is a three-step cycle.

First, you identify the highest-leverage, delegatable tasks that will enable growth; next, you hire the good person to do those tasks; finally, you give them space to do their jobwork together closely to build organizational capacity. Over time, the organization starts to have capacity in that area, independent of the founder’s hands-on involvement, which frees up time to…identify the set of high-leverage, delegatable tasks that will enable the next phase of growth.

On the surface, it’s a simple positive-feedback loop. In practice, each step is very difficult to pull off.

Your parcel of high-leverage, delegatable tasks has to be relatively stable, so that you are investing in capacity the company will need over the long-run. You need to define the tasks well enough to delegate them — describe the key responsibilities, articulate what good looks like, assess the level of skills and experience required to do the job well. You have to bundle together responsibilities into a job that potential employees want to take, at a wage you’re prepared to pay.

Then you must actually find the right person for the job. Hiring well is important and difficult; whole books could be written on the subject. Here we will just acknowledge that and jump to the third, make-or-break step: building organizational capacity.

It doesn’t matter how senior or experienced your new hire is. The capacity you are building is specific to your company and your goals. You are teaching the new leader to act in your stead, so that their judgement can substitute for yours. That is the only way to complete the cycle. It requires close collaboration over months and years, providing them with scaffolding, context, and feedback to perform their job. Capacity building is more labour-intensive than just doing the job yourself, and at times you will be tempted to take over, because it is faster and easier and less frustrating to do it yourself. Resist. Tie yourself to the mast. When long-term capacity building is your goal, you must strike the perfect balance between hands-on and taking the reins; between giving space and giving enough rope to hang.

With time, the new leader will internalize the founder’s sensibilities. Their judgement will align with the company’s strategy and ethos. They will be able to take on more and more scope with more and more independence. This has not happened by magic or osmosis — it has happened through hands-on, day-to-day interactions around the work. Gradually, the founder realizes she has a bit more breathing room, a bit more time to think. She has hired a good person; she has built new organizational capacity.

And now, the cycle can begin anew: the founder starts to identify the next bundle of high-leverage tasks that will enable growth, and starts to build organizational capability in a whole new domain.

Founder Mode is building capacity wherever it’s most needed to unlock growth. It’s also self-limiting, because it depends on something in fixed supply: the founder’s time and attention. Some founders are more skilled than others at capacity building. Most founders will improve the more they do it. But the really powerful thing about Founder Mode is that it’s fractal. Once the company’s capacity has crossed a certain threshold, other leaders in the company can “do” Founder Mode. Those leaders are not only professional managers, but keepers of the company’s ethos, able to work with others to build still more capacity.

Humans are bad at understanding exponential curves. Putting in the effort to build capacity in a few individuals feels like it can’t possibly deliver massive growth. This is a rocketship! We have to move faster than that! And it’s true that at first, Founder Mode is slow. However, the investment in those first few leaders turns them into capacity builders too. That replicates throughout the organization over years, until one day you look up, and sure enough, the company is in Manager Mode: lots of good people, all being given space to do their jobs.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Asking for Help

The asymmetry of asking for help, autonomous vs. dependent help-seeking, and what it means for organizational effectiveness.

Podcast: Building Alignment with Co-Creation

Workomics appears on the Storylinking podcast. Susan Bartlett discusses building alignment with co-creation with host Tom Lietz.

Hierarchy, knowledge work, and gender equality

Flat hierarchy ismore effective for modern knowledge work, but recent research shows it might contribute to gender inequality