Let’s begin with a concept from social philosopher Christopher Nguyen: value capture.

Value capture occurs when an agent’s values are rich and subtle; they enter a social environment that presents simplified — typically quantified — versions of these values; and those simplified articulations come to dominate their practical reasoning.

The agent is you. Your rich and subtle values are particular to you, but let’s say that some of these are in the ballpark:

- “Work hard, but also have time to relax and hang with friends.”

- Do good work that makes a difference for people.

- Learn new skills and improve existing ones.

- Enjoy collaborating with colleagues on interesting projects.

- Earn enough money to support myself and do fun things.

The social environment you have entered is the workplace. Your workplace no doubt has many different values, but there is one simplified, quantified value that is present in almost every workplace and has been since the dawn of industrialization: the number of hours you spend at work.

In many jobs, that value is quite explicit: workers are paid by the hour, or the company bills by the hour. But even in those cases, the number of hours you spend at work is not what is truly valued, either by organizations or individuals. The true values are more subtle and more nuanced, harder to quantify, harder to assess.

“Hours worked” is not an unreasonable simplification. It can be compared across different kinds of jobs. It is readily observable and trackable. There is a non-inverse relationship between hours worked and output produced.

However, it’s a much worse simplification than it used to be.

When all work happened at a physical workplace, it was easier to observe and track. When more kinds of work were grounded in physical and mechanical throughput, the relationship between hours worked and output was more direct and predictable.

For modern knowledge workers, the relationship between “hours at work” and “value of work produced” is quite tenuous. You can be in back-to-back meetings from 8am to 6pm, and produce very little in the way of valued output. You can have a creative breakthrough in the shower, when you’re not really “working.” The hours you spend sitting at your laptop or being present in a physical office are poor predictors of value produced.

Even so, there are countless jobs where the relationship between hours and value remains tightly linked. ER doctors and ICU nurses must be in the hospital with patients. Teachers must be in the classroom with students. Waitstaff and chefs must be in the restaurant with diners. “Being present and available” is a primary source of value, quite apart from whatever gets accomplished during that time. The same is true for those knowledge workers having breakthroughs in the shower. Nowadays, it relies less on physical proximity, but being present and available for clients, colleagues, and internal customers is valuable in and of itself.

What is not valuable is “hours spent at work.” It’s an example of pure value capture: for generations, we have organized work around a simplified, easy-to-count proxy. It dominates our thinking, making it more difficult to find new ways of approaching flexible work, because we have lost sight of what really matters.

A values-driven approach to flexible work

At Workomics, our work is flexible-by-design. You can work from home. You can work from the office. You can log in from Mexico or Thailand or the UK*. You can get a haircut or head to the gym or meet your contractor in the middle of the day. You can start your workday at 10:43 am. You can leave at 3:15pm. Our employment agreements do not actually specify a required number of hours at work each week. Instead, we say this:

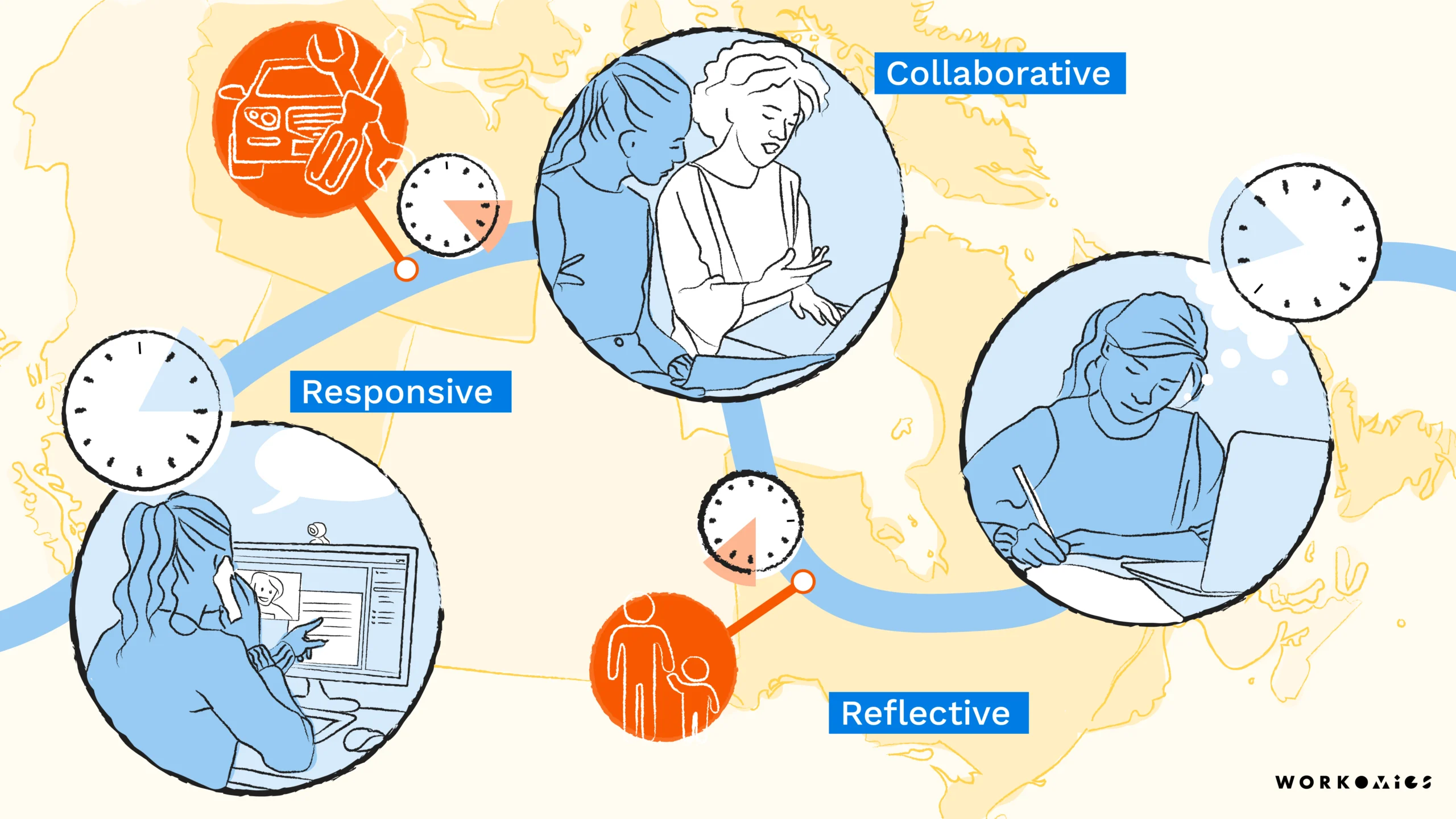

Workomics team members and clients live and work across North American time zones. The shape of the work changes day-by-day: sometimes it calls for independent heads-down time, sometimes it requires high levels of responsiveness, sometimes it demands intense collaboration. You should be sufficiently connected so that your availability and responsiveness does not impede your colleagues’ productivity, the quality of your work, or the satisfaction of your clients. As a rough guideline, most days you should plan to be available for meetings and synchronous collaboration for at least six hours between 8am and 9pm Eastern Time.

As a policy, it’s unusually non-prescriptive on when work happens and how much of it you need to do. We loosely suggest that “most days” you should be working at least 6 hours inside a wide 13-hour window. But the bulk of the policy is focused on what we really value — that people are structuring their work days so that the work is high quality, the clients are happy, and no one’s progress is blocked because someone else is getting a haircut.

It’s also a policy that requires good faith on both sides. If employees take it as an invitation to do as little work as possible, or employers take it as freedom to regularly expect responsiveness at 8:30pm, the whole system breaks down.

Several things enable this level of flexibility:

Vast swaths of predictability. If you know what your deliverables are, when they are due, and what good looks like, then flexibility is easier. And indeed, Workomics puts considerable effort into rigorous project planning with realistic contingencies specifically so we can have the level of predictability we need to work so flexibly. For their part, employees accept the project schedules as natural limitations on flexibility, and adjust their schedules to meet deadlines and attend key meetings.

Nonetheless, we are a client services business, which means we are often faced with changing or emerging client needs that require responsiveness or adaptiveness. Our flexible work needs to be balanced with reciprocity and shared accountability for outcomes. Last month, we had a big deliverable that required a last-minute, weekend push, and there wasn’t a person in the company who wasn’t logging in over the weekend to pitch in and get the work done. The company affords employees enormous flexibility as long as the work gets delivered. The employees reciprocate that same level of flexibility in the rare cases it’s required to do the work.

Our day-to-day flexibility is enabled by a counterbalancing rigidity for paid time off. Vacation must be formally requested and approved via email. Planned days off are tracked centrally, and we stop accepting requests for weeks that are over-subscribed. We do this because flexible work is much harder when a team is short-staffed: there are fewer people to cover the gaps or handle any surprises. In order to maintain flexibility for people who aren’t on vacation, and to have vacations where people can be fully disconnected for multiple weeks, planned absences need to be carefully managed.

Finally, we recognize the limits of our baseline flexibility. Because there are deliverables and deadlines (sometimes aggressive!), because there is an expectation of reciprocity, so that sometimes work bleeds into personal time; because there is less flexibility in time off, it’s hard to fully segregate work time from personal time. And yet many of our staff want to have dedicated chunks of time where they can teach or take a course, pursue a creative project, or further a business venture. For those cases, we offer more formal flexible work arrangements. In those cases, employees take pro-rated pay and benefits, in exchange for protected time where they know they will not have to be present and available.

It’s hard to break free of value capture. When a sick kid or a renovation takes up most of your day, you still tend to think in terms of “making up the hours.” You need to regularly remind yourself that the important thing is delivering the work and meeting the deadlines. But if we want to really grapple with flexible work, we can’t focus narrowly on the number of hours, when you start and stop, or where you sit to do the work. Individuals value a wide array of things — yes, the ability to dictate their own schedule and balance personal and work priorities. But they also value work they feel proud of, camaraderie and collaboration, learning and growth, helping others (colleagues, clients) achieve goals. Policies for flexible work should reflect the breadth of those values and how best to achieve them within the confines of a given business model.

* As long as you are temporarily visiting those places. We cannot handle the tax and employment law implications of employees who aren’t legal residents of specific Canadian provinces.

Our other ideas worth exploring

GenAI, capitalism, and human flourishing

How capitalism breaks down in the face of GenerativeAI, and why we need to find ways to optimize for human flourishing.

Balancing the pursuit of new

Organizations tend to focus on building new things. But there is a season to turn inwards, prioritizing and optimizing what already exists.

Asking for Help

The asymmetry of asking for help, autonomous vs. dependent help-seeking, and what it means for organizational effectiveness.