Customer experience — delivering holistic, well-orchestrated interactions that anticipate customer needs and exceed their expectations — typically focuses on, well, the customer. Makes sense. It’s right there in the name. So organizations that want to ‘do’ customer experience invest in things like customer research, customer journey maps, UX capabilities. These are all helpful tools, but often they don’t end up changing much about how customers actually experience a product or service. And that’s because the hard part of customer experience isn’t really the customer side. It’s the organizational logic.

Organizational logic is the set of norms, assumptions, processes, and shared vocabulary that help people in an organization get work done. It overlaps with organizational culture, but is both a bit more specific and a bit more expansive. Organizational logic doesn’t include elements of culture that aren’t central to how work gets done (e.g. dress code, after-work drinks). Conversely, organizational logic does include those arcane procedural details that aren’t about culture, like “system x only accepts data in format y.” In essence, organizational logic is the collective mental model that allows dozens or hundreds or thousands of people to work together and get something out into the world.

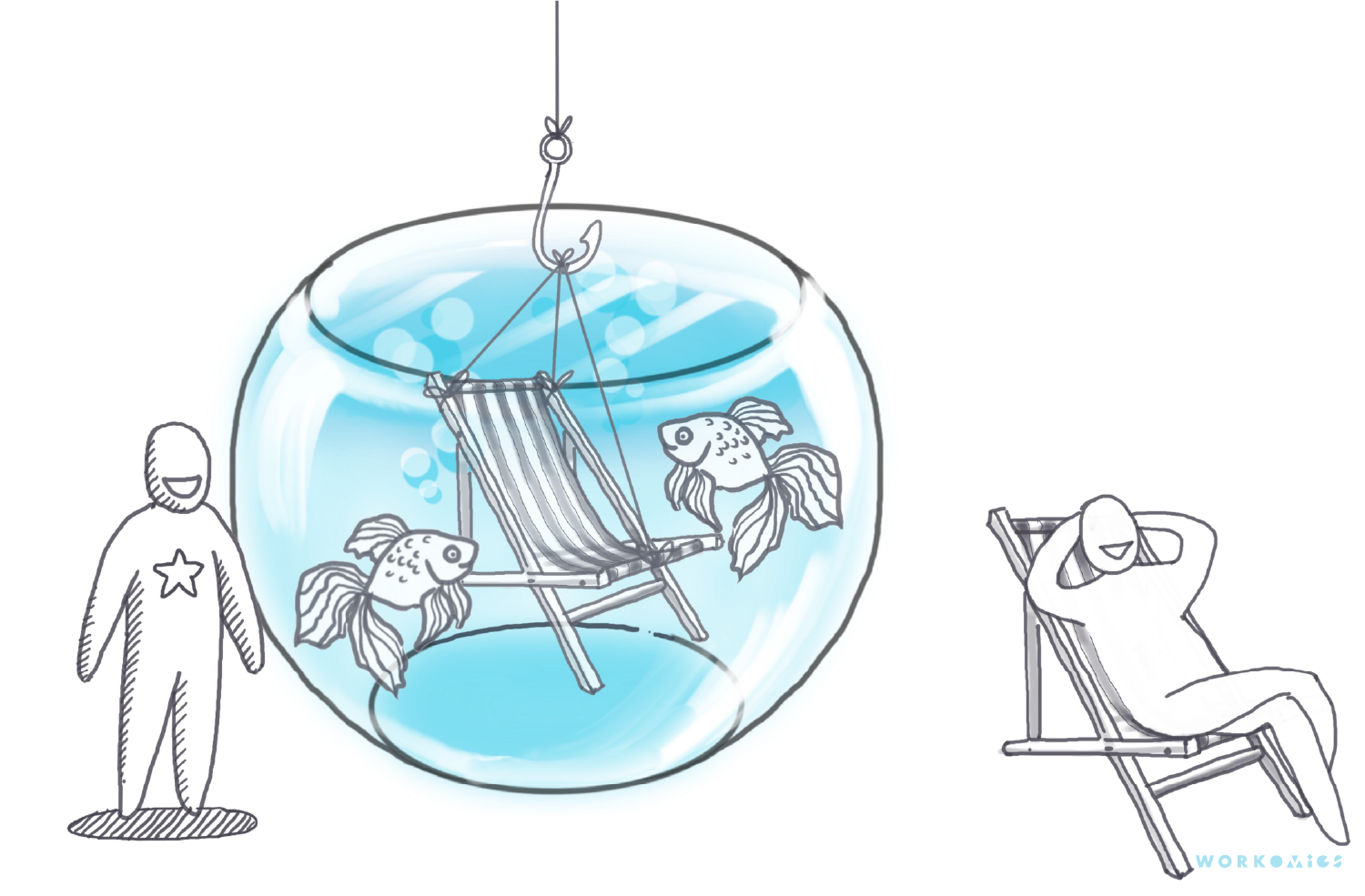

When you first join a new organization, you feel its logic very acutely, because you haven’t internalized it. Hour by hour, in ways large and small, you encounter differences between the norms and definitions you’ve accumulated in your past life, and the ones that permeate in this new place. The process of onboarding is really about you assimilating, so that you can operate with the same logic as everyone else. Once you do that, you stop noticing the organizational logic — it’s just your default. You become a fish and the organizational logic is the water you’re swimming in.

Organizational logic is essential to getting work done. You couldn’t have a company without it, any more than fish can flourish out of water. But when it comes to customer experience, that organizational logic is problematic. We make decisions about the customer experience we offer, and we take the water for granted — we forget it’s even there. Meanwhile, our customers are on the outside needing to get into full scuba gear, because they aren’t fish and they don’t live in the water.

And this is why customer experience initiatives can struggle to see results. It doesn’t matter how much you talk to your customers or how many journey maps you make, if you can’t recognize when your organizational logic is getting in your customers’ way.

Even when customer research does a good job of identifying unmet needs, organizational logic can make us oblivious to the barriers for customer adoption.

When customer experience gets reduced to customer research and customer journey maps, you can end up jumping through a series of ostensibly customer-centric hoops without actually addressing the customers’ core needs. Customer research only looks for solutions that fit within the existing organizational logic. Journey maps end up buttressing an organization-centric worldview that says customers are somehow intrinsically interested in following your tidy process, rather than hiring a product or service to do a job. The end result is customers end up putting on scuba gear and dealing with something janky and watery because the organization is prioritizing its own logic over customer needs.

But organizations need organizational logic as surely as fish need water, so it’s not something you can eliminate. Meanwhile, your customers will never be swimming in your fishbowl. That ongoing tension is what makes customer experience hard — the need to take something necessary and pervasive to internal employees, and figure out how to make it invisible to external customers.

Customer experience, then, is about helping everyone in the organization:

- Be aware of the water;

- Notice when it the water negatively affecting customers; and

- Make different decisions so the customer doesn’t have to deal with the water.

That means individuals need to build new intuitions about their role and develop the skill of switching between customer and organizational perspectives, so they can make different trade-offs and different decisions. That’s step one.

If your team makes video tutorials, organizational logic will tend you towards addressing customer challenges with video tutorials.

Step two is coordinating those different decisions and trade-offs cross-functionally. In all but the smallest organizations, it takes collaboration across multiple teams and silos to deliver a customer experience. By definition, these more customer-centric decisions depart from the existing organizational logic. Without coordination, different teams will make different trade-offs, creating a customer experience that is even more disjointed and watery. Instead of making organizational logic invisible to customers, you’ll be highlighting its dysfunction.

It takes a lot of discipline and perseverance to do this kind of cross-functional intuition-building. At almost every turn, people tend to default to the path of least organizational resistance. It’s an awful lot easier for a team to tackle some customer research or make a journey map. But the core work of customer experience is much more mundane, and thankless: stakeholdering and communicating (and communicating again); setting up task forces and cross-functional forums that add enough value that people actually want to show up; doing the work while giving others the credit; and sustaining that effort over months and years, until the new ways of working are truly established in the organizational logic.

It’s not very sexy and it’s not for the faint of heart, but it’s the only thing we’ve found that can deliver sustained customer experience excellence over the long run.

When teams collaborate cross-functionally, they are more likely to find solutions that customers really need.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Mailbag: Social Change and Career Choice

In general, the more a job is focused on contributing to society and community, the less it pays. It’s not an immutable law of physics, but wages in the charitable sector consistently lag the private sector, and typically there’s a trade-off between doing good (for the world) and doing well (for yourself, financially.)

Three principles to make AI work for people and teams

Meet Daisy: An AI Case Study. Daisy is a Regional Sales Enablement Specialist for a large multinational in a heavily regulated industry. She works with sales executives in her region to help them build skills and deliver better outcomes for customers and the business.

An AI Policy-in-Progress

We use AI judiciously, so that we are minimizing the downsides and maximizing the benefit. Our use of AI should be additive, transparent, eco-conscious, and voluntary.