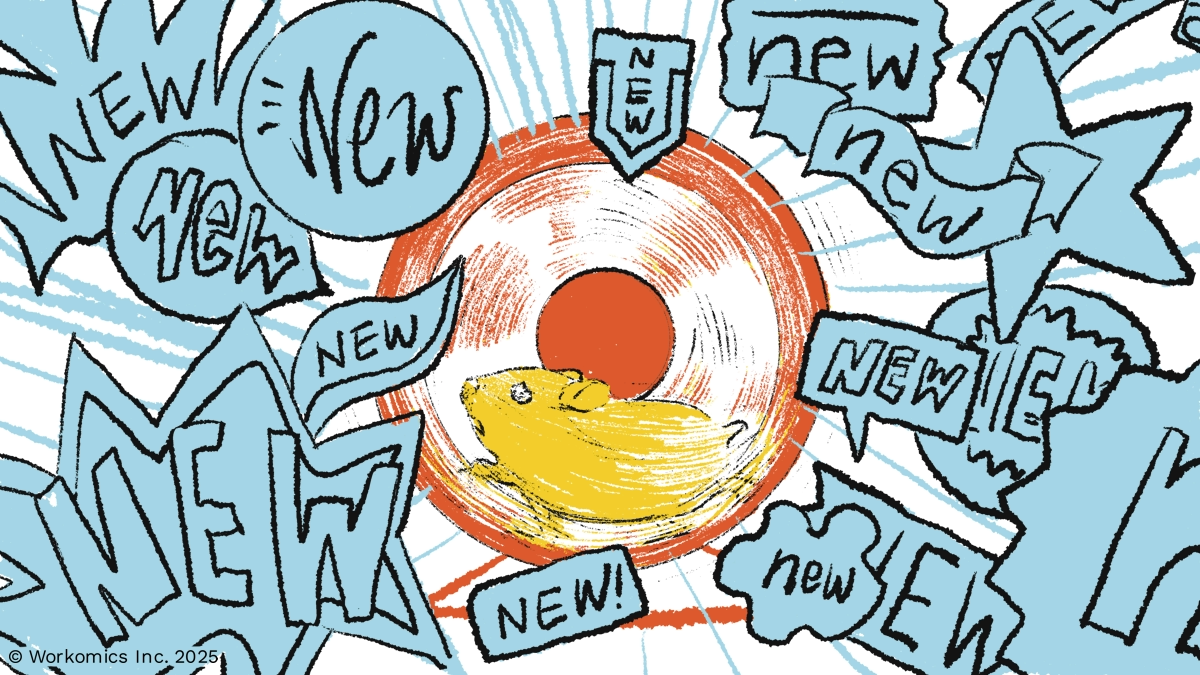

That’s not to say organizations always excel at new. Execution and results can range from terrible to outstanding. But regardless of outcome, new is organizations’ comfort zone. They have a roadmap and milestones to follow, all on the path to delivering the next new thing.

The trouble with not-new

Suppose you ask the questions, and realize you are past the point of diminishing marginal returns. In fact, you should just double down on your two or three most successful tactics, exactly as they are today, and drop everything else. Not because those tactics are perfect, but because any money you spend improving them won’t result in new revenue.

That might be the right thing for the business, but when it comes time to hand out bonuses, raises, and promotions, “I did the best thing for the business,” almost always loses out to “I made a shiny new thing.” And so, products have bloated features, sales teams are overwhelmed with infinite offerings, and someone always seems to be redoing the positioning (again).

There is a real cost to these misaligned incentives. The organization spends money on things that don’t add commensurate value. But also, complexity incurs a cost in and of itself, and one that is rarely accounted for.

Balancing with Prioritize-and-Optimize

These kinds of incentives can only be changed at the institutional level. Organizations need to make it okay — even celebrated — to be in prioritize-and-optimize mode. It’s truly a great accomplishment: you’ve done a great job at making a new and shiny gadget. And now the reward is that you get to shift into Prioritize-and-Optimize. Make it a thing.

As part of making it a thing, you’ll need to rethink your measurement. When it isn’t neglected entirely, measurement tends to focus on whether a tactic met its goal as a standalone initiative. That’s what matters in new. But in Prioritize-and-Optimize, we’re interested in whether a tactic delivers better than others, and whether it justifies its opportunity costs. To answer those questions effectively, we have to collect different data, so that we can compare across tactics and contextualize results with their opportunity costs.

Prioritize-and-optimize should also come with a strong bias towards pruning activities and tactics. People are loss-averse, so they hate to take things away. But the inherent costs of complexity mean you should err on the side of ruthlessness. “What did you stop doing this year?” should be the key question in Prioritize-and-Optimize, and it should almost always have an answer.

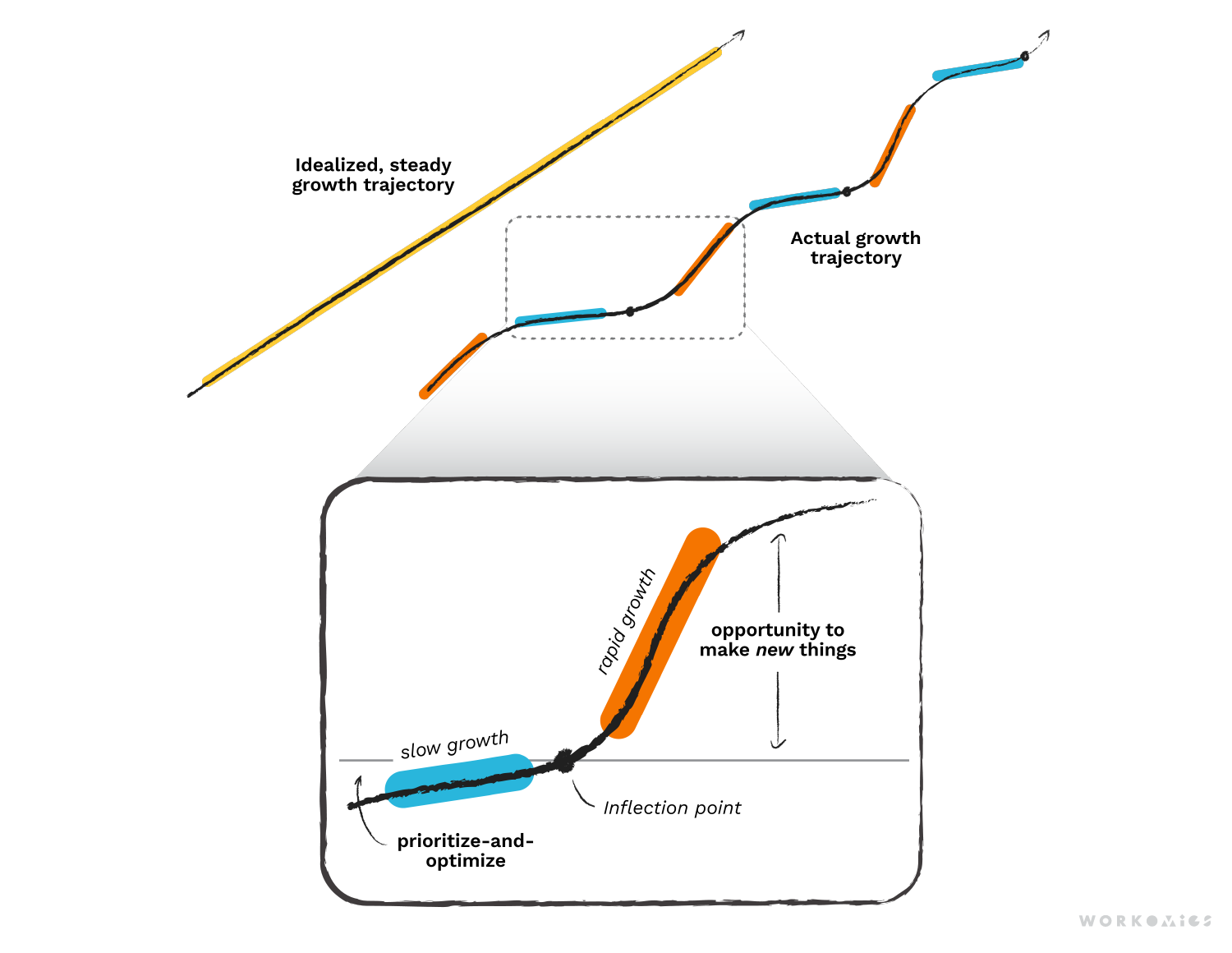

Likewise, Prioritize-and-Optimize is not a permanent state for any given area of the business. Markets change. New competitors enter. Technology opens up a game-changing possibility. Inevitably, there will be new inflection points to capitalize on, and it’s critical not to miss them because you were in Prioritize-and-Optimize. In many ways, inflection points are easier to spot when the team is not consumed by delivering something new. But false positives are a real risk, where the bias to new leads you to switch out before you’ve really had a chance to optimize or prune anything. Organizations need a way to evaluate when to switch back to making new. The most effective criteria will be outward-looking, so that you are switching into new in response to specific changes in the needs of your customers, or broader market dynamics.

We think of growth as a steady upward phenomenon; the reality is less uniform. Inflection points create opportunities for rapid growth and new initiatives, in between slower growth phases when we would be better to prioritize and optimize.

The point is that organizations are programmed for new by default. In any initiative, there is going to be a point of diminishing marginal returns. Organizations rarely recognize it, and rarely respond to it by doing less. They pour the same amount of effort (and expense) into new, even when the possible payoff is markedly less. Deliberate reprogramming to make Prioritize-and-Optimize a valued state of being, is one way to overcome the bias towards new, and find a better balance.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Podcast: Building Alignment with Co-Creation

Workomics appears on the Storylinking podcast. Susan Bartlett discusses building alignment with co-creation with host Tom Lietz.

Hierarchy, knowledge work, and gender equality

Flat hierarchy ismore effective for modern knowledge work, but recent research shows it might contribute to gender inequality

How Founder Mode Evolves into Manager Mode

Founder Mode is building capacity wherever it’s most needed to unlock growth. Manager Mode is about running a company in a stable equilibrium.