- You might worry about rejection. The person you ask might say, “no,” and that feels bad, and still leaves you needing help.

- Even if the person says yes, you might worry about imposition. Perhaps others experience your request for help as an inconvenience or a burden.

- You might worry that asking for help projects a lack of competence or self-reliance. The act of asking highlights some kind of personal gap or deficit.

Ick.

But here’s the interesting thing: asking for help is asymmetrical. We are liable to worry about these negative outcomes when we are the asker. But if you instead imagine yourself as the askee — the person receiving the request — your first instinct is usually quite the opposite. When people ask us for help, we want to provide it. We are happy to help.

- Overestimated the possibility of rejection. Almost everyone who was asked to help agreed right away. In broad observational studies, the rate of “request fulfillment” is as high as 88%. Generally, when you ask for help, people will say yes.

- Underestimated how positive helpers would feel about helping, and misattributed their reasons for helping. 74% of requestors in the study thought people would agree to help out of some sense of social pressure or obligation, but only 2% of helpers reported feeling that way. Helpers generally helped because they wanted to, and felt positive for having helped.

What about being perceived as incompetent? Here again, people’s intuition is 180˚ from what psychologists have found in field experiments. Asking someone for help or advice makes them think you are more competent. This is especially so if you are asking for help on a difficult task, or in an area where the person you are asking has expertise. But don’t stress too much: researchers found that asking for help with easy tasks doesn’t have negative effects on how people perceive your competence either.

Psychology field experiments are not the real world, and there are certainly other studies that have more mixed results with different variables. But consistently across the literature, we are too pessimistic in our expectations of how others will respond to requests for help. We underestimate how much people want to help, and how much positive feeling they derive from helping. In many cases, asking for and receiving help is a win-win, but our own misaligned expectations create a barrier towards asking.

The best kind of help-seeking at work

When it comes to the workplace, not all requests for help are created equal.

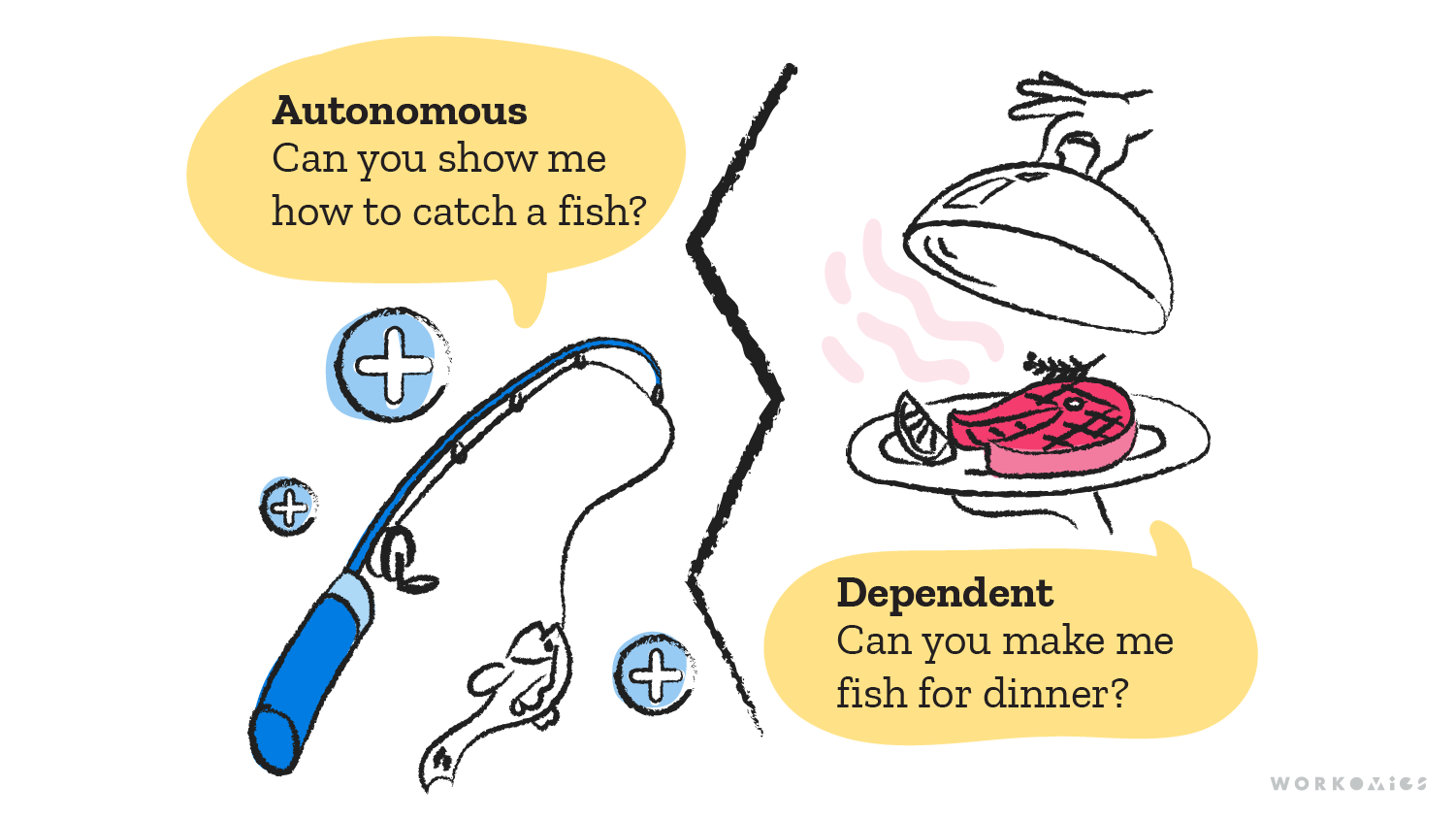

Researchers distinguish two different kinds of help requests. Autonomous help-seeking is when you are asking for help in building knowledge and skills that will allow you to level up your capabilities. Think of it as asking for coaching or professional development (“teach me to fish”). Over the long-run, autonomous help-seeking lets you tackle similar challenges independently. Dependent help-seeking, by contrast, is more short-term focused: you are looking for immediate assistance, rather than building your own capabilities. This kind of help-seeking is asking someone else to take care of something on your behalf (“give me fish”).

What is surprising is some recent research showing that autonomous vs. dependent help-seeking is not an artifact of individuals. Rather, people seek help based on the environments they work in and the kinds of stressors that are causing them to seek help.

Autonomous help-seeking as a sign of organizational health

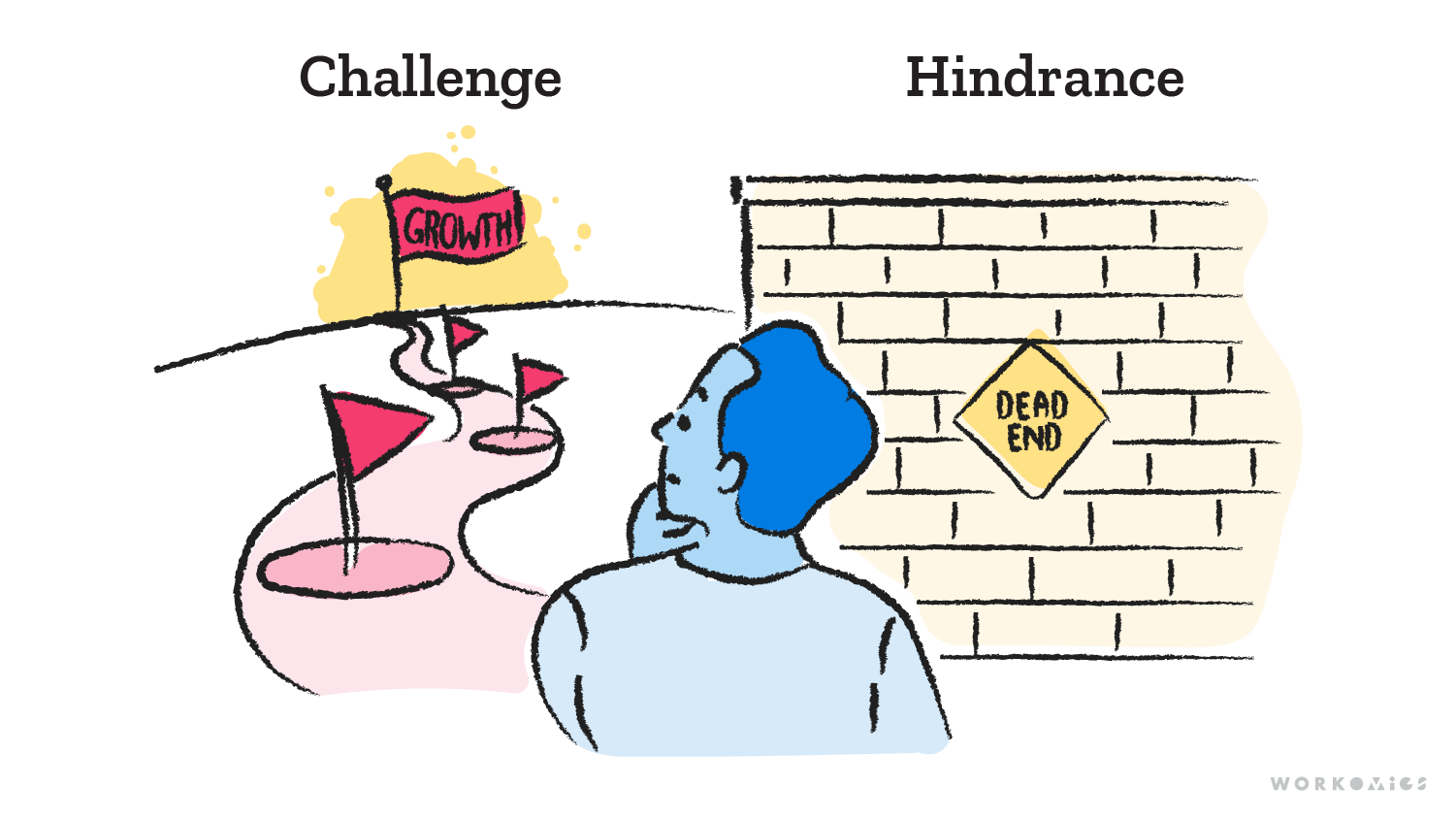

If you need help because of factors like complex work, level of responsibility, or time pressure (“challenge stressors,” in the researchers’ parlance), you will tend to engage in autonomous help-seeking. People perceive challenge stressors as opportunities for learning and growth, so the long-term capability-building of autonomous help-seeking is a natural fit.

In contrast, if you need help because of things like role ambiguity, red tape, or office politics (“hindrance stressors”), you will tend towards dependent help-seeking. Hindrance stressors drive people to focus on meeting the minimum requirements without incurring penalties, so help-seeking is short-term and utilitarian.

With this lens, we can see autonomous help-seeking is a strong signal of organizational effectiveness. When you regularly see that kind of help-seeking it means that people:

- Are challenged in their roles.

- Feel psychologically safe enough to ask for help where they need it.

- Avoid the inefficiency and churn that comes from struggling solo with a challenge.

- Grow and learn, increasing organizational capability overall

- Are not unduly burdened with needless obstacles to completing their jobs.

Many organizations are attuned to psychological safety as an important cultural baseline. Without that sense of safety, people don’t feel they can admit to errors or gaps, and they won’t ask for help. Psychological safety is an important area of focus, but this recent research suggests that organizations must do more. If you want the right kind of help-seeking, you need to minimize hindrance stressors. Red tape, politics, and role ambiguity are not just minor annoyances. They are the enemies of productive, growth-oriented, autonomous help-seeking, and have an outsized impact on your culture.

In short, we should strive to create a culture and climate where asking for help is the norm, and support our teams in asking for help more often. But equally, we should stamp out bureaucratic inefficiencies and so that people are challenged by the work itself, rather than the obstacles in their way.

Our other ideas worth exploring

Mailbag: Social Change and Career Choice

In general, the more a job is focused on contributing to society and community, the less it pays. It’s not an immutable law of physics, but wages in the charitable sector consistently lag the private sector, and typically there’s a trade-off between doing good (for the world) and doing well (for yourself, financially.)

Three principles to make AI work for people and teams

Meet Daisy: An AI Case Study. Daisy is a Regional Sales Enablement Specialist for a large multinational in a heavily regulated industry. She works with sales executives in her region to help them build skills and deliver better outcomes for customers and the business.

An AI Policy-in-Progress

We use AI judiciously, so that we are minimizing the downsides and maximizing the benefit. Our use of AI should be additive, transparent, eco-conscious, and voluntary.